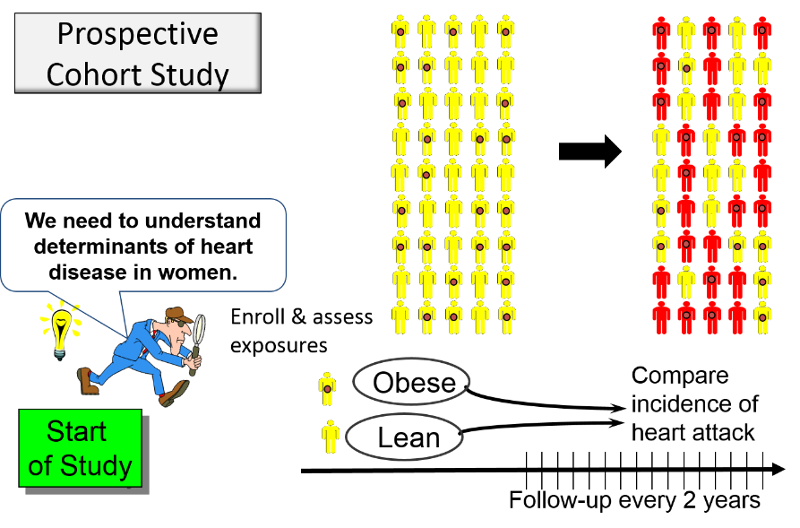

Prospective Cohort Studies

Cohort studies can be classified as prospective or retrospective based on when outcomes occurred in relation to the enrollment of the cohort. The Framingham Heart Study is an example of a prospective cohort study. Another well-known prospective cohort study is the Nurses' Health Study. The original Nurses' Health Study (NHS) began in 1976 by enrolling about 121,000 female nurses from across the United States who were initially free of known cardiovascular disease or cancer. (The Nurses' Health Study is now enrolling the third generation cohort, which includes male and female nurses).

In a prospective study like the Nurses Health Study baseline information is collected from all subjects in the same way using exactly the same questions and data collection methods for all subjects. The investigators design the questions and data collection procedures carefully in order to obtain accurate information about exposures before disease develops in any of the subjects.

The distinguishing feature of a prospective cohort study is that, at the time that the investigators begin enrolling subjects and collecting baseline exposure information, none of the subjects has developed any of the outcomes of interest.

After baseline information is collected, the participants are followed "longitudinally," i.e. over a period of time, usually for years, to determine if and when they become diseased and whether their exposure status changes. Most studies of this type contact the participants periodically, perhaps every two years, to update information on exposures and outcomes. In this way, investigators can eventually use the data to answer many questions about the associations between exposures ("risk factors") and disease outcomes. For example, one NHS study examined the association between smoking and breast cancer and found that there was no significant association.

Another NHS study examined the association between obesity and myocardial infarction. They used reported height and weight to calculate BMII and categorized women into five categories of BMI. The table below summarizes their findings with respect to non-fatal myocardial infarction.

| BMI | # non-fatal MIs | Person-Years | Inc. Rate Per 10,000 P-Y | Rate Ratio |

| >=30 | 85 | 99,573 | 85.4 | 3.7 |

| 25.0-29.9

|

67 | 148,541 | 45.1 | 1.6 |

| 23.0-24.9 | 56 | 155,717 | 36.0 | 1.6 |

| 20.0-22.9 | 57 | 194,243 | 29.3 | 1.3 |

| <20 | 41 | 177,356 | 23.1 | 1.0 |

The data above are from Willett WC, Manson JE, et al.: Weight, weight change, and coronary heart disease in women. Risk within the 'normal' weight range. JAMA. 1995 Feb 8;273(6):461-5.

Potential Pitfall: Analysis of prospective cohort studies can take place only after enough time has elapsed so that a sufficient number of subjects have developed the outcomes of interest. Since the data analysis occurs after some outcomes have occurred, some students mistakenly would call this a retrospective study, but this is incorrect. The analysis always occurs after a certain number of events have taken place. The characteristic that distinguishes a study as prospective is that the subjects were enrolled, and baseline data were collected before any subjects developed an outcome of interest.

Potential Pitfall: Analysis of prospective cohort studies can take place only after enough time has elapsed so that a sufficient number of subjects have developed the outcomes of interest. Since the data analysis occurs after some outcomes have occurred, some students mistakenly would call this a retrospective study, but this is incorrect. The analysis always occurs after a certain number of events have taken place. The characteristic that distinguishes a study as prospective is that the subjects were enrolled, and baseline data were collected before any subjects developed an outcome of interest.

Follow Up in Prospective Cohort Studies

Ideally, investigators want to have complete follow-up on all subjects, but in large cohort studies that run for years, there are inevitably people who become lost to follow up as a result of death, moving, or simply loss of interest in participating. When this occurs, the investigators know the subject's exposure status prior to losing them, but not their outcome.

The biggest problem with substantial loss to follow up (LTF) is that it can bias the results of the study if the losses are different for one of the exposure-outcome categories. This will be illustrated in the module on bias.

There is no way to know if the losses are different for one of the exposure-outcome categories, so the only strategy to minimize bias from loss to follow up is to keep follow up high (in both prospective cohort studies and clinical trials).

Strategies to Maintain Follow Up

- Choosing subjects who are motivated

- Choosing subjects who are easy to track (e.g., registered nurses or physicians)

- Keeping subjects interested with newsletters and incentives;

- Being courteous and making them feel that they are members of a research "family"

- Frequent phone calls

- Making questionnaires easy to fill out