Compliance and Loss to Follow Up

Non-compliance is the failure to adhere to the study protocol. For example, in the Physicians Health Study about 15% of the subjects randomized to receive low-dose aspirin did not regularly take the capsules they received, and about 15% of the subjects in the placebo group were actually taking aspirin on a fairly regular basis.

Effects of Non-compliance:

Non-compliance tends minimize any difference between the groups. As a result, the statistical power to detect a true difference is reduced, and the true effect will be biased toward the null.

Ways to Maintain Compliance

- Design protocols and regimens that are as simple and easy as possible to follow and comply with. For example, use give pills in convenient "blister packs" with the days of the month on the pack, or use special pill boxes to make it easier to remember to take medications.

- Enroll motivated and knowledgeable subjects who lead fairly organized lives (e.g. The Physicians' Health Study or The Nurses's Health Study).

- Paint an accurate picture of what will be required during the enrollment and informed consent process.

- During enrollment take a careful medical history to try to identify individuals who would have a difficult time complying, and exclude these people. For example, The Physicians' Health Study excluded subjects with a history of gastritis, since they would be less likely to tolerate the aspirin regimen and at higher risk of ulcers and gastritis.

- When possible, mask the subjects in the comparison group, because if they know they are not receiving an active ingredient, they will be less likely to comply

- Have your study staff contact subjects frequently to maintain interest and motivation.

- Conduct a "run-in phase" to identify subjects who are unable or unmotivated to comply.

Assessing Compliance

Even when measures are taken to maximize compliance, it is important to assess compliance in the participants.

- Ask the subjects if they adhered to the protocol.

- Collect pill packs to count unused pills.

- Collect blood or urine samples to assess compliance (measure the active ingredient or an inert marker if possible.)

Loss to Follow Up

Follow up on subjects can be accomplished through periodic visits and examinations, by phone interviews, by mail questionnaires, or via the Internet. Patients may drop out of a study as a result of loss or interest, adverse reactions, or simple a burdensome protocol that becomes tiring. Others might become lost to follow up because of death, relocation or other reasons. Loss to follow up is a problem for two main reasons:

- It reduces the effective sample size because the investigators will be missing outcome measures on those who are lost.

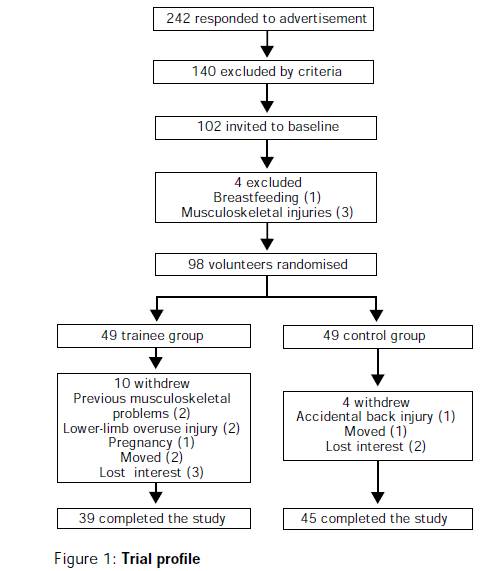

- If follow up rates differ among comparison groups and if attrition is related to the outcome, the results of the study can be biased. This is a special type of selection bias caused not by differences in enrollment, but instead by differential rates of retention that are related to the outcome. For example, a study on the efficacy of high-impact exercise on risk factors for osteoporosis had greater loss to follow-up in the group assigned to exercise (see below). Women who dropped out may have had inherently lower bone strength that made the high-impact regimen less tolerable for them. If so, this would have produced selective loss of women more likely to develop osteoporosis from the active treatment group, and this would cause a biased estimate, specifically an overestimate of the benefit of exercise.