Blinding (Masking), Placebos, and Shams

Blinding (or masking) refers to withholding knowledge about treatment assignment from subjects and/or investigators in order to prevent bias in assessment of subjective outcomes, such as pain relief. There are several schemes for blinding:

- Single blind: subjects don't know which treatment they are receiving

- Double blind: neither subjects nor the investigator who is assessing the patient are aware of the treatment assignment until the end of the study

- Triple blind: This term is sometimes used when the person who administers treatment to the study subjects is kept unaware of the assigned treatment.

Blinding is facilitated by the use of placebo treatments or sham procedures

treatments or sham procedures . For example, in a study designed to evaluate the efficacy of arthroscopic surgery in treating painful osteoarthritis of the knee, subjects in the sham surgery group had a small incision placed on the knee under sedation, but arthroscopic surgery was not actually performed. Instead, the surgeons simulated the procedure by asking to be given the usual instruments and manipulating the knee of the subject as if the real procedure were being performed. Sham surgery is more problematic than use of a placebo, because it has the potential for causing harm and because the patient is being actively deceived. (For a detailed discussion on the ethics of sham surgeries, see Miller FG and Kaptchuk TJ: Sham procedures and the ethics of clinical trials. J R Soc Med. 2004 December; 97(12): 576–578.)

. For example, in a study designed to evaluate the efficacy of arthroscopic surgery in treating painful osteoarthritis of the knee, subjects in the sham surgery group had a small incision placed on the knee under sedation, but arthroscopic surgery was not actually performed. Instead, the surgeons simulated the procedure by asking to be given the usual instruments and manipulating the knee of the subject as if the real procedure were being performed. Sham surgery is more problematic than use of a placebo, because it has the potential for causing harm and because the patient is being actively deceived. (For a detailed discussion on the ethics of sham surgeries, see Miller FG and Kaptchuk TJ: Sham procedures and the ethics of clinical trials. J R Soc Med. 2004 December; 97(12): 576–578.)

- Placebo: a pharmacologically inert (inactive) substance that is otherwise indistinguishable from the active treatment. When a certain "standard of care" is routine for a given condition, it is probably not ethical to assign subjects to a placebo group.

- Sham: similar to a placebo, a sham is a fake procedure designed to resemble a real procedure that is being tested for efficacy.

Masking is not always necessary, nor is it always possible. If the primary outcome of interest is definitive and objective, such as death, then masking isn't necessary. In addition, if the treatment is an elaborate surgical procedure, the ethics of doing a sham procedure would be questionable.

The Placebo Effect

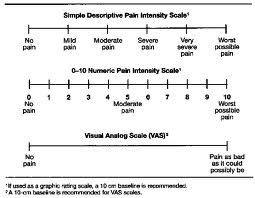

The use of placebos and sham procedures facilitates masking and thereby prevents bias in assessment of subjective outcomes, such as pain relief. However, another major advantage to using them is that they enable investigators to distinguish the degree to which improvements are solely the result of the "placebo effect." When people are enrolled in a study, or prescribed a medication or offered any medical treatment or care, there is generally an expectation that they will improve or benefit from it. The tendency for people to report improvements even when the treatment has no real therapeutic effect is referred to as "the placebo effect," and it can vary widely in magnitude. In a clinical trial designed to test the effectiveness of glucosamine and chondroitin in relieving symptoms of osteoarthritis the authors defined the outcome of interest as greater than 20% relief of pain on an analog scale, shown below.

In the placebo treated group, 60% reported greater than 20% relief of pain, compared to 67% in the group treated with glucosamine and chondroitin.

Another illustration of the potential impact of the placebo effect is seen in the article below from the New York Times.

|

Perceptions: Positive Spin Adds to a Placebo's Impact By NICHOLAS BAKALAR, New York Times, December 27, 2011 In a study published online last week in the online journal PLoS One, researchers explained to 80 volunteers with irritable bowel syndrome that half of them would receive routine treatment and the other half would receive a placebo. They explained to all that this was an inert substance, like a sugar pill, that had been found to "produce significant improvement in I.B.S. symptoms through mind-body self-healing processes." The patients, all treated with the same attention, warmth and empathy by the researchers, were then randomly assigned to get the pill or not. At the end of three weeks, they tested all the patients with questionnaires assessing the level of their pain and other symptoms. The patients given the sugar pill — in a bottle clearly marked "placebo" — reported significantly better pain relief and greater reduction in the severity of other symptoms than those who got no pill. The authors speculate that the doctors' communication of a positive outcome was one factor in the apparent effectiveness of the placebo. |

Does Sugar Make Kids Hyperactive?

Watch this short video.