Control of Gene Expression

By gene expression we mean the transcription of a gene into mRNA and its subsequent translation into protein. Gene expression is primarily controlled at the level of transcription, largely as a result of binding of proteins to specific sites on DNA. In 1965 Francois Jacob, Jacques Monod, and Andre Lwoff shared the Nobel prize in medicine for their work supporting the idea that control of enzyme levels in cells is regulated by transcription of DNA. occurs through regulation of transcription, which can be either induced or repressed. These researchers proposed that production of the enzyme is controlled by an "operon," which consists a series of related genes on the chromosome consisting of an operator, a promoter, a regulator gene, and structural genes.

- The structural genes contain the code for the proteins products that are to be produced. Regulation of protein production is largely achieved by modulating access of RNA polymerase to the structural gene being transcribed.

- The promoter gene doesn't encode anything; it is simply a DNA sequence that is initial binding site for RNA polymerase.

- The operator gene is also non-coding; it is just a DNA sequence that is the binding site for the repressor.

- The regulator gene codes for synthesis of a repressor molecule that binds to the operator and blocks RNA polymerase from transcribing the structural genes.

The operator gene is the sequence of non-transcribable DNA that is the repressor binding site. There is also a regulator gene, which codes for the synthesis of a repressor molecule hat binds to the operator

- Example of Inducible Transcription: The bacterium E. coli has three genes that encode for enzymes that enable it to split and metabolize lactose (a sugar in milk). The promoter is the site on DNA where RNA polymerase binds in order to initiate transcription. However, the enzymes are usually present in very low concentrations, because their transcription is inhibited by a repressor protein produced by a regulator gene (see the top portion of the figure below). The repressor protein binds to the operator site and inhibits transcription. However, if lactose is present in the environment, it can bind to the repressor protein and inactivate it, effectively removing the blockade and enabling transcription of the messenger RNA needed for synthesis of these genes (lower portion of the figure below).

- Example of Repressible Transcription: E. coli need the amino acid tryptophan, and the DNA in E. coli also has genes for synthesizing it. These genes generally transcribe continuously since the bacterium needs tryptophan. However, if tryptophan concentrations are high, transcription is repressed (turned off) by binding to a repressor protein and activating it as illustrated below.

Source: http://biowiki.ucdavis.edu/Under_Construction/BioStuff/BIO_101/Reading_and_Lecture_Notes/Control_of_Gene_Expression_in_Prokaryotes

Control of Gene Expression in Eukaryotes

Eukaryotic cells have similar mechanisms for control of gene expression, but they are more complex. Consider, for example, that prokaryotic cells of a given species are all the same, but most eukaryotes are multicellular organisms with many cell types, so control of gene expression is much more complicated. Not surprisingly, gene expression in eukaryotic cells is controlled by a number of complex processes which are summarized by the following list.

- After fertilization, the cells in the developing embryo become increasingly specialized, largely by turning on some genes and turning off many others. Some cells in the pancreas, for example, are specialized to synthesize and secrete digestive enzymes, while other pancreatic cells (β-cells in the islets of Langerhans) are specialized to synthesis and secrete insulin. Each type of cell has a particular pattern of expressed genes. This differentiation

into specialized cells occurs largely as a result of turning off the expression of most genes in the cell; mature cells may only use 3-5% of the genes present in the cell's nucleus.

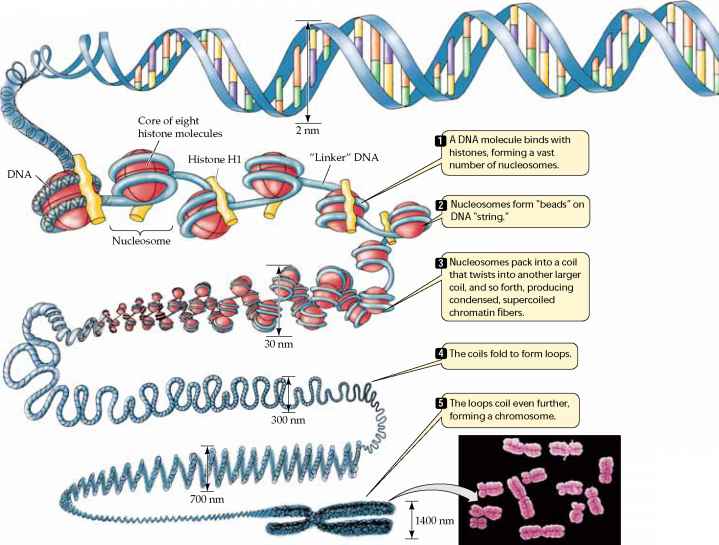

into specialized cells occurs largely as a result of turning off the expression of most genes in the cell; mature cells may only use 3-5% of the genes present in the cell's nucleus. - Gene expression in eukaryotes may also be regulated through by alterations in the packing of DNA, which modulates the access of the cell's transcription enzymes (e.g., RNA polymerase) to DNA. The illustration below shows that chromosomes have a complex structure. The DNA helix is wrapped around special proteins called histones, and this are wrapped into tight helical fibers. These fibers are then looped and folded into increasingly compact structures, which, when fully coiled and condensed, give the chromosomes their characteristic appearance in metaphase

.

.

Source: http://www.78stepshealth.us/plasma-membrane/eukaryotic-chromosomes.html

- Similar to the operons described above for prokaryotes, eukaryotes also use regulatory proteins to control transcription, but each eukaryotic gene has its own set of controls. In addition, there are many more regulatory proteins in eukaryotes and the interactions are much more complex.

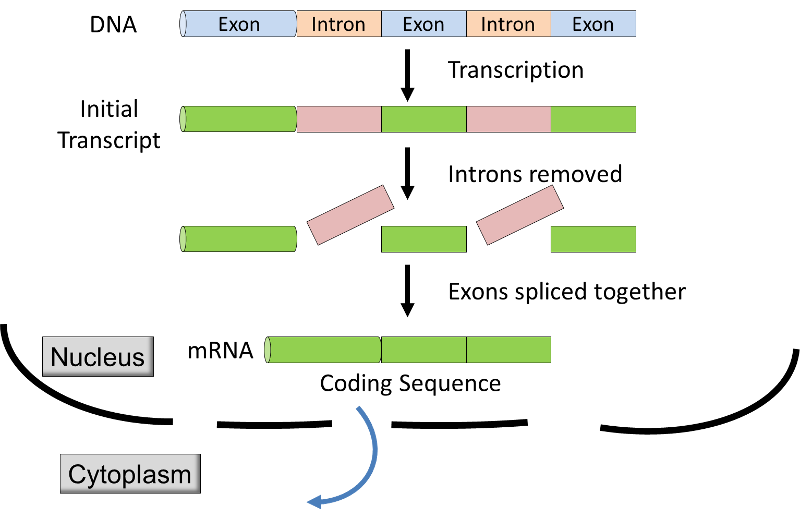

- In eukaryotes transcription takes place within the membrane-bound nucleus, and the initial transcript is modified before it is transported from the nucleus to the cytoplasm for translation at the ribosome s. The initial transcript in eukaryotes has coding segments (exons

) alternating with non-coding segments (introns). Before the mRNA leaves the nucleus, the introns are removed from the transcript by a process called RNA splicing (see graphic & video below), and extra nucleotides are added to the ends of the transcript; these non-coding "caps" and "tails" protect the mRNA from attack by cellular enzymes and aid in recognition by the ribosomes.

) alternating with non-coding segments (introns). Before the mRNA leaves the nucleus, the introns are removed from the transcript by a process called RNA splicing (see graphic & video below), and extra nucleotides are added to the ends of the transcript; these non-coding "caps" and "tails" protect the mRNA from attack by cellular enzymes and aid in recognition by the ribosomes.

Source: http://unmug.com/category/biology/organisation-control-of-genome/

- Variation in the longevity of mRNA provides yet another opportunity for control of gene expression. Prokaryotic mRNA is very short-lived, but eukaryotic transcripts can last hours, or sometimes even weeks (e.g., mRNA for hemoglobin in the red blood cells of birds).

- The process of translation offers additional opportunities for regulation by many proteins. For example, the translation of hemoglobin mRNA is inhibited unless iron-containing heme is present in the cell.

- There are also opportunities for "post-translational" controls of gene expression in eukaryotes. Some translated polypeptides (proteins) are cut by enzymes into smaller, active final products. as illustrated in the figure below which depicts post-translational processing of the hormone insulin. Insulin is initially translated as a large, inactive precursor; a signal sequence is removed from the head of the precursor, and a large central portion (the C-chain) is cut away, leaving two smaller peptide chains which are then linked to each other by disulfide bridges.The smaller final form is the active form of insulin.

Source: http://www.nbs.csudh.edu/chemistry/faculty/nsturm/CHE450/19_InsulinGlucagon.htm

- Gene expression can also be modified by the breakdown of the proteins that are produced. For example, some of the enzymes involved in cell metabolism are broken down shortly after they are produced; this provides a mechanism for rapidly responding to changing metabolic demands.

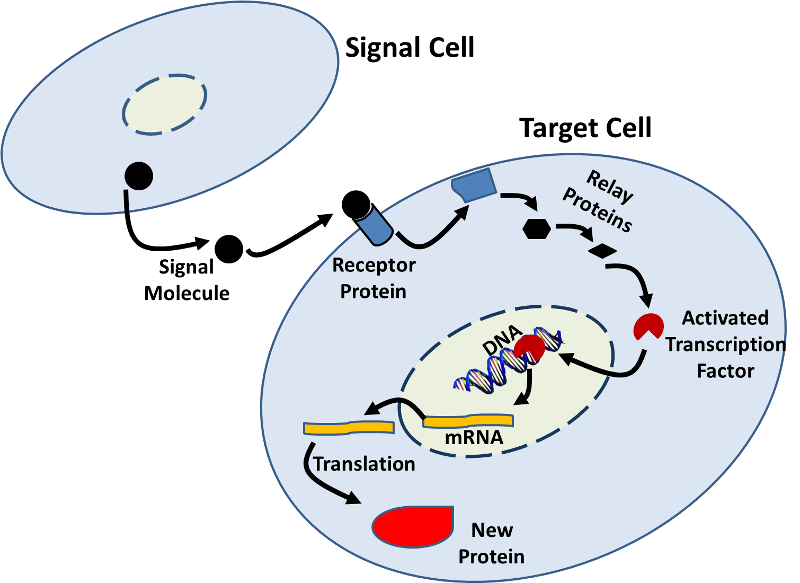

- Gene expression can also be influenced by signals from other cells. There are many examples in which a signal molecule (e.g., a hormone) from one cell binds to a receptor protein on a target cell and initiates a sequence of biochemical changes (a signal transduction pathway) that result in changes within the target cell. These changes can include increased or decreased transcription as illustrated in the figure below.

Source: http://sites.saschina.org/emily01px2016/2014/11/23/a-variety-of-intercellular-and-intracellular-signal-transmissions-mediate-gene-expression/

- The RNA Interference system (RNAi) is yet another mechanism by which cells control gene expression by shutting off translation of mRNA. RNAi can also be used to shut down translation of viral proteins when a cell is infected by a virus. The RNAi system also has the potential to be exploited therapeutically.

RNAi

Some RNA virus will invade cells and introduce double-stranded RNA which will use the cells machinery to make new copies of viral RNA and viral proteins. The cell's RNA interference system (RNAi) can prevent the viral RNA from replicating. First, an enzyme nicknamed "Dicer" chops any double-stranded RNA it finds into pieces that are about 22 nucleotides long. Next, protein complexes called RISC (RNA-induced Silencing Complex) bind to the fragments of double-stranded RNA, winds it, and then releases one of the strands, while retaining the other. The RISC-RNA complex will then bind to any other viral RNA with nucleotide sequences matching those on the RNA attached to the complex. This binding blocks translation of viral proteins at least partially, if not completely. The RNAi system could potentially be used to develop treatments for defective genes that cause disease. The treatment would involve making a double-stranded RNA from the diseased gene and introducing it into cells to silence the expression of that gene. For an illustrated explanation of RNAi, see the short, interactive Flash module at http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/body/rnai-explained.html

The RNA interference system is also explained more completely in the video below from Nature Video.