Conditions Necessary for Confounding

There are three conditions that must be present for confounding to occur:

- The confounding factor must be associated with both the risk factor of interest and the outcome.

- The confounding factor must be distributed unequally among the groups being compared.

- A confounder cannot be an intermediary step in the causal pathway from the exposure of interest to the outcome of interest.

For example, it is known that modest alcohol consumption is associated with a decreased risk of coronary heart disease, and it is believed that one of the mechanisms by which alcohol causes a reduced risk is that alcohol raises blood levels of HDL, the so called "good cholesterol." Higher levels of HDL are known to be associated with a reduced risk of heart disease. Consequently it is believed that modest alcohol consumption raises HDL levels, and this, in turn, reduces coronary heart disease. In a situation like this HDL levels are not confounder of the association between alcohol and heart disease, because it is part of the mechanism by which alcohol produces this beneficial effect. If increased HDL is a consequence of alcohol consumption and part of the mechanism by which it lowers the risk of heart disease, then it is not a confounder..

![]()

Not surprisingly, since most diseases have multiple contributing causes (risk factors), there are many possible confounders.

- A confounder can be another risk factor for the disease. For example, in the hypothetical cohort study testing the association between exercise and heart disease, age is a confounder because it is a risk factor for heart disease.

- Similarly a confounder can also be a preventive factor for the disease. If those people who exercised regularly were more likely to take aspirin, and aspirin reduces the risk of heart disease, then aspirin use would be a confounding factor that would tend to exaggerate the benefit of exercise.

- A confounder can also be a surrogate or a marker for some other cause of disease. For example, socioeconomic status may be a confounder in this example because lower socioeconomic status is a marker for a complex set of poorly understood factors that seem to carry a higher risk of heart disease.

As a result, there may be many possible confounding factors that could influence an association. For example, in looking at the association between exercise and heart disease, other possible confounders might include age, diet, smoking status and a variety of other risk factors that might be unevenly distributed between the groups being compared.

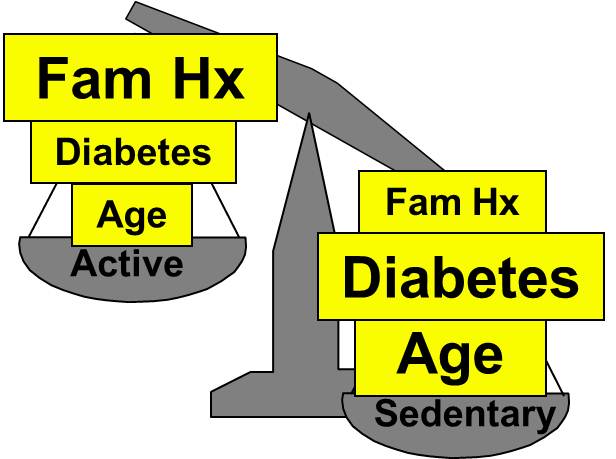

Aside from their physical inactivity, sedentary subjects may be more likely to smoke, to have high blood pressure and diabetes, and to consume diets with a higher fat content; all of these factors would tend to increase the risk of coronary heart disease. On the other hand, subjects who go to a gym regularly (active) may be more likely to be males and perhaps more likely to have a family history of heart disease, i.e., factors that might increase the risk of active subjects. Consequently, there may be many confounders that can distort the estimate of association in one direction or another.

|

|

Active |

Sedentary |

|---|---|---|

|

Age |

46 ± 1.4 |

59 ± 1.5 |

|

Dietary Fat % |

29 ± 5.0 |

42 ± 7.0 |

|

Current Smokers |

5% |

24% |

|

Hypertension |

8% |

17% |

|

Diabetes |

2% |

9% |

|

Family History of Heart Disease |

25% |

5% |

|

Males |

60% |

40% |

Identifying Confounding

- A simple, direct way to determine whether a given risk factor caused confounding is to compare the estimated measure of association before and after adjusting for confounding. In other words, compute the measure of association both before and after adjusting for a potential confounding factor. If the difference between the two measures of association is 10% or more, then confounding was present. If it is less than 10%, then there was little, if any, confounding. How to do this will be addressed in greater detail below.

- Other investigators will determine whether a potential confounding variable is associated with the exposure of interest and whether it is associated with the outcome of interest. If there is a clinically meaningful relationship between an the variable and the risk factor and between the variable and the outcome (regardless of whether that relationship reaches statistical significance), the variable is regarded as a confounder.

- Still other investigators perform formal tests of hypothesis to assess whether the variable is associated with the exposure of interest and with the outcome.

Effects of Confounding

- May account for all or part of an apparent association.

- May cause an overestimate of the true association (positive confounding) or an underestimate of the association (negative confounding).

The magnitude confounding can be quantified by computing the percentage difference between the crude and adjusted measures of effect. There are two slightly different methods that investigators use to compute this, as illustrated below.

Percent difference is calculated by calculating the difference between the starting value and ending value and then dividing this by the starting value. Many investigators consider the crude measure of association to be the "starting value".

- Method Favored by Biostatisticians

Other investigators consider the adjusted measure of association to be the starting value, because it is less confounded than the crude measure of association.

- Method Favored by Epidemiologists

While the two methods above differ slightly, they generally produce similar results and provide a reasonable way of assessing the magnitude of confounding. Note also that confounding can be negative or positive in value.