Selection Bias in Cohort Studies and Clinical Trials

Prospective Cohort Studies and Clinical Trials

In the previous examples selection bias occurred because selection or enrollment procedures resulted in over- or under-representation of one or more of the exposure-disease categories. Since prospective cohort studies enroll subjects who have not yet developed the health outcomes of interest, selection bias due to enrollment procedures is rare, but can occur. In addition, prospective cohort studies can have selection bias as a result of differential retention during follow up.

Blood clots that form in the deep veins in the leg can break loose from the venous system and be carried back to the right side of the heart and then to the pulmonary artery where they become lodged and disrupt pulmonary circulation. This is referred to as pulmonary thromboembolism. It is a serious and sometimes fatal event, and some oral contraceptives (OC) have been shown to increase the risk of thrombosis (clot formation in the veins), particularly in older formulations of oral contraceptives.

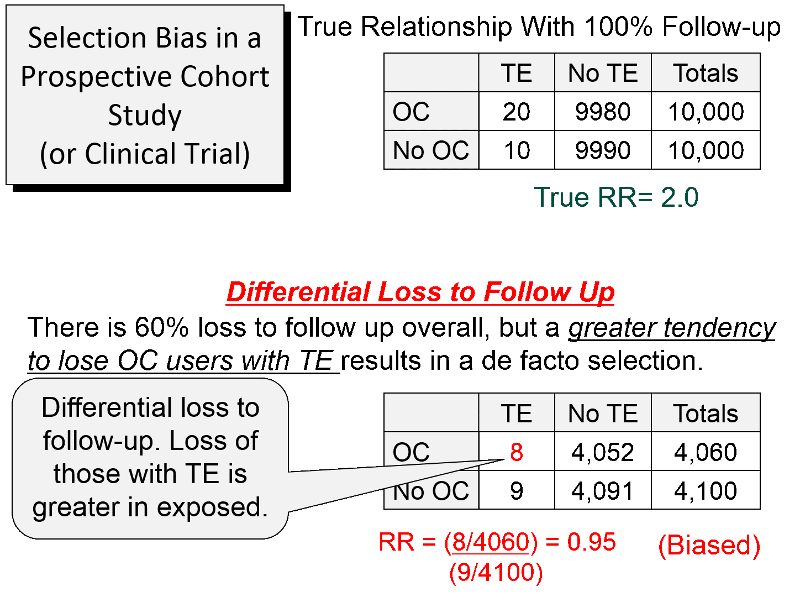

Consider a hypothetical prospective cohort study of the association between use of oral contraceptives (OC) and development of pulmonary thromboembolism (TE) in women of child-bearing age, as summarized in the figure below. The contingency table at the top shows what the results would have been if there had been complete follow up. There are 10,000 subjects in each group, and 20 out of 10,000 OC users developed TE compared to 10 out of 10,000 women who did not use OC, so the true RR=2.0.

About 60% of the subjects were lost to follow up, as shown in the lower portion of the figure. However, there was differential loss to follow up, since 12 out the 20 women with TE were lost in the OC groups, but only one out of the 10 women with TE in the group not using OCs were lost. In the case-control study discussed above there was over-representation in one of the cells of the table, but here there is under-representation because of greater loss to follow up in women who had both the exposure and the outcome of interest. So, in this prospective cohort study, the sample that is available for analysis is not representative of the source population of women of child-bearing age. The result is a biased estimate from the sample which gives RR=0.95, suggesting no association, even though there is a two-fold increase in risk.

This form of selection bias (bias from differential loss to follow up) can occur in both prospective cohort studies and clinical trials if there are substantial losses to follow up. There is no way of knowing whether loss to follow up is differential, but if follow up rates are greater than 80%, the effects of this form are selection bias are likely to be minimal. The only way to avoid this type of bias is for investigators to do whatever they can to maintain high rates of follow up. If loss to follow up is much greater than 20%, one needs to be increasingly concerned that the estimate might be biased.

Selection Bias in Retrospective Cohort Studies

In a retrospective cohort study selection bias occurs if selection of either exposed or non-exposed subjects is somehow related to the outcome. For example, if researchers are more likely to enroll an exposed person if they have the outcome of interest, the measure of association will be biased.

Example:

Researchers wanted to conduct a retrospective cohort study on the health effects of an occupational exposure to an organic solvent in a factory using employee health records. The truth is that those exposed to the solvent had a two-fold increase in liver damage, and if they had had all of the records, the contingency table would have looked like the table below.

|

True |

Diseased |

Non-diseased |

Total |

|

Exposed |

100 |

900 |

1000 |

|

Unexposed |

50 |

950 |

1000 |

RR= (100/1,000)/(50/1,000) = 2.0

Unfortunately, many of the employee records had been lost or destroyed over the past 20 years. However, there had been suspicions about the health effects of the solvent for many years, and the records of employees who had been exposed and developed health problems were more likely to have been retained. Records were available for 98% of the employees who had been exposed and developed liver damage, but for all other employees only 80% of the records could be found. As a result, the contingency table looked like this.

|

Biased |

Diseased |

Non-diseased |

Total |

|

Exposed |

98 |

720 |

818 |

|

Unexposed |

40 |

760 |

800 |

RR= (98/818)/(40/800) = 2.4

Here, the source population consisted of the employees of the factory, and once again, the data in the sample was not representative of the source population. Specifically, one exposure-disease category had greater retention of records than the others, so the measure of association was biased. In a sense, loss of records in this retrospective cohort study is analogous to differential loss to follow up in prospective cohort studies and clinical trials.