Elements of a Cause

Three Essential Attributes of a Cause

- Association: variation in a causal factor must result in a change in probability of the outcome; if X changes, Y changes

- Time order: a cause must precede the effect; can be either proximate (e.g.; food poisoning) or distant (e.g.; carcinogen)

- Direction: the exposure results in the outcome, not vice versa.

The Sufficient-Component Cause model

In 1976 Professor Ken Rothman, who is a member of the epidemiology faculty at Boston University School of Public Health, proposed a conceptual model of causation known as the "sufficient-component cause model" in an attempt to provide a practical view of causation which also had a sound theoretical basis.

Rothman recognized that disease outcomes have multiple contributing determinants that may act together to produce a given instance of disease. For example, exposure to someone who has TB does not necessarily result in the occurrence of TB; other conditions such as proximity to an infected person, frequency and duration of exposure, ventilation, nutritional status, and immune status also play a role in determining whether active TB will develop. Moreover, the set of determinants that produce TB in one individual may not be the same set of conditions that were responsible for the occurrence of TB in others.

Rothman defined a sufficient cause as "...a complete causal mechanism" that "inevitably produces disease." Consequently, a "sufficient cause" is not a single factor, but a minimum set of factors and circumstances that, if present in a given individual, will produce the disease.

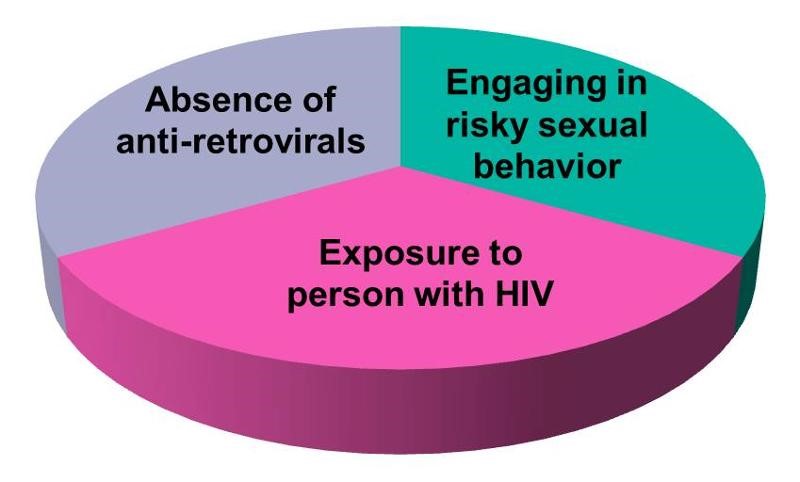

Aschengrau and Seage use the example of causation of AIDS. A sufficient cause for AIDS might consist of the following components:

- exposure to an individual with HIV

- repeatedly engaging in risky sexual behavior with that individual

- absence of antiretroviral drugs that reduce viral load of HIV

The pie chart below might be used to represent the sufficient cause model for this scenario.

This model suggests that the presence of these three component causes is sufficient to produce AIDS in this individual. Note further that if any one of these components were absent, AIDS would not occur. Hence, Rothman asserts that a cause is an event, condition, or characteristic without which the disease would not have occurred. Note that the sufficient cause illustrated here is only one manner in which AIDS could occur. Different individuals will have different sets of individual components that combine to produce a sufficient cause (i.e., a case of AIDS).

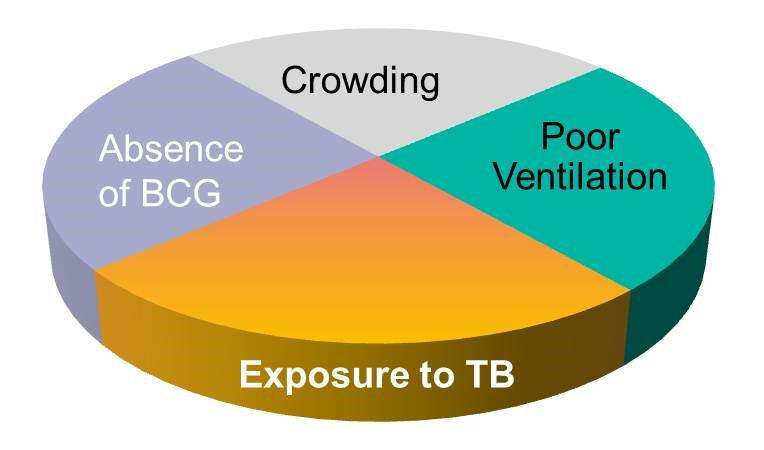

If one were to apply the sufficient-component cause model to tuberculosis (TB), one possible cause might be represented by the pie chart below.

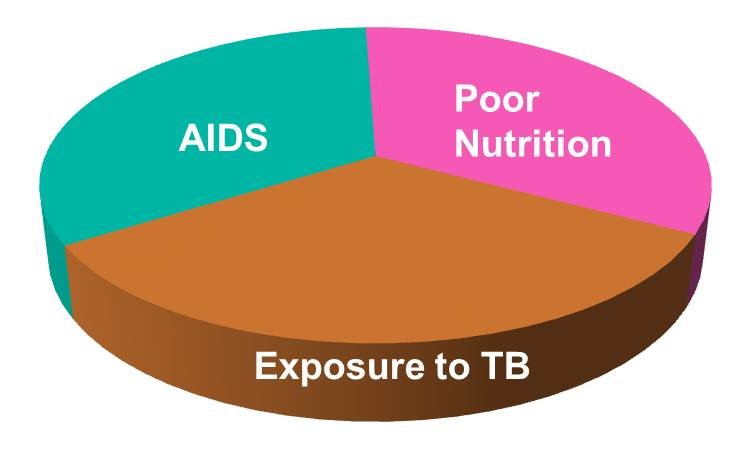

There may, however, be many sufficient causes of TB which may differ in their components, although some components might be shared among different sufficient causes. Consider, for example, the two sufficient causes below.

Note that exposure to TB is a component in all three of the causal models above, reflecting the fact that TB will not develop without exposure to the TB bacillus. Exposure to the TB bacillus is therefore a necessary, but not solely sufficient component cause. Other causal components must also be present for TB to occur.

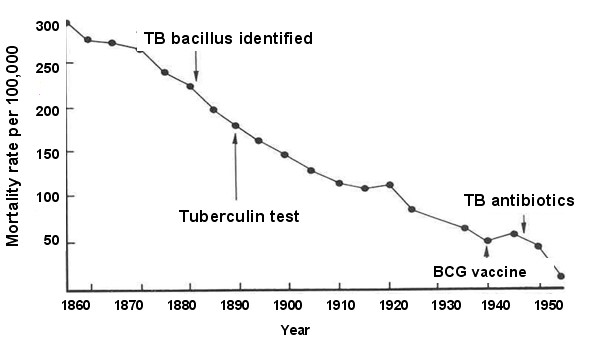

Thinking about the causes of TB in this fashion underscores the complexity of disease pathogenesis, but it also alerts us to multiple opportunities to prevent disease, because removing any one of the components in a sufficient cause prevents the occurrence of disease. This perhaps provides an explanation for the remarkable decline in TB mortality in the United Kingdom during the 19th and 20th century. The line graph below shows the annual mortality from TB per 100,000 population from 1850 to 1960.

During this time span, the introduction of "the hygienic idea" and the subsequent development of public health initiatives led to gradual improvements in living conditions, including less crowding, better ventilation, and better nutrition. The decreased prevalence of these components is likely to have been responsible for the steady decline in TB mortality seen during this period. Note, however, the two points on the line graph that correspond to World War 1 and World War 11 when there are temporary increases in TB mortality. It is well known that the wars had a widespread impact on the population and that nutrition suffered and people were sometimes seeking shelter in bomb shelters that were poorly ventilated and crowded. The sufficient-component model to the left offers a coherent explanation for the steady decline in TB mortality over time and the temporary increases seen during war time.