This page is adapted from the module entitled "Dealing with Stress in Disasters" at the Local Public Health Institute of Massachusetts. (Link to the LPHI module)

What is Stress?

This page is copied from the Local Public Health Institute of Massachusetts module at the following link: Link to Building Psychological Resilience for Dealing with Disasters.

Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines stress as: "a physical, chemical, or emotional factor that causes bodily or mental tension, and may be a factor in disease causation." If you were to ask people to explain what stress is and how it affects them, you would likely get a wide variety of definitions. Many factors and situations have the potential to impact us in stressful ways, but it is important to note our individual perceptions and responses to these stimuli.

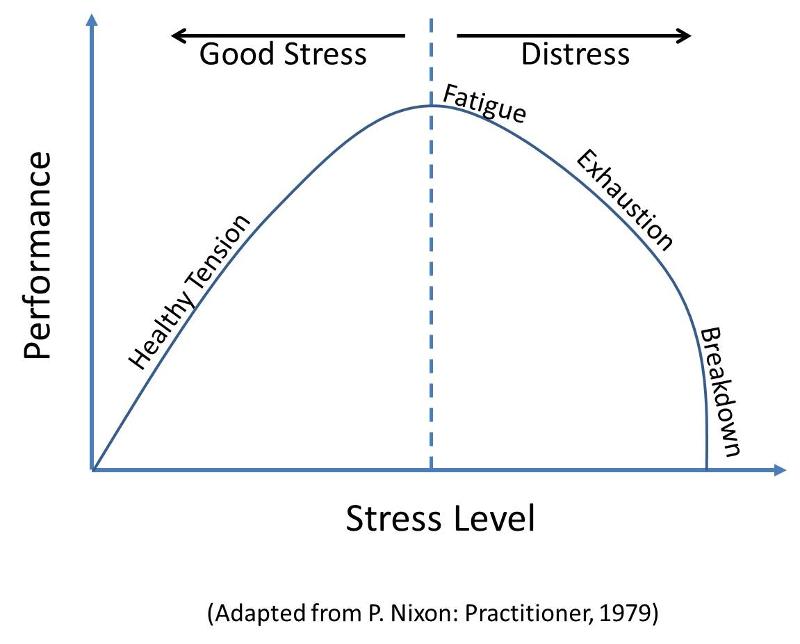

Athletes and performers often describe mental tension that arises prior to a contest or a performance, as anxiety or outright fear. Nevertheless, they acknowledge that this tension can both overwhelm the individual and result in a disastrous performance, or it can be the source of a positive response that brings out the very best in people. The graphic below attempts to illustrate both the potentially motivating effects of stress and the adverse effects of excessive or prolonged stress combined with poor coping skills (on the right).

Although we frequently have little control over stressful factors and situations, it is possible to train yourself to modulate your thoughts, emotions, and your environment in ways that help you to deal with the problems you encounter, rather than allowing events take control of you. Conceptually, your efforts to develop psychological resilience can expand your range of good stress and shrink the range of debilitating stress. This is what is meant by building psychological resilience, and it is particularly important for public health workers and emergency responders.

The Stress Reaction

French physiologist Claude Bernard was the first to introduce the concept of dynamic equilibrium, or steady state. Organisms, even individual cells within organisms, are subject to never-ending changes in conditions. But in order to survive and maintain optimal function, built-in mechanisms respond to altered conditions (stresses) by making adjustments that are designed to re-establish equilibrium. As a simple example, if the external temperature rises, our bodies automatically perspire - a compensatory response that reduces our internal temperature.

Neurologist Walter Cannon applied the term homeostasis to this concept of dynamic equilibrium. Cannon was the first to propose that stressors could be emotional as well as physical, and he described the "fight or flight " response that occurs when animals are threatened with immediate danger (a severe stress). Hans Selye, another scientist, extended Cannon's observation and discovered that the "fight or flight" response is mediated by the secretion of powerful neurotransmitters. Stimuli from the brain also cause the hypothalamus

" response that occurs when animals are threatened with immediate danger (a severe stress). Hans Selye, another scientist, extended Cannon's observation and discovered that the "fight or flight" response is mediated by the secretion of powerful neurotransmitters. Stimuli from the brain also cause the hypothalamus to release corticotrophin releasing factor (CRF). CRF then causes the secretion of adrenocorticophic hormone (ACTH) from the pituitary gland

to release corticotrophin releasing factor (CRF). CRF then causes the secretion of adrenocorticophic hormone (ACTH) from the pituitary gland at the base of the skull. ACTH travels to the adrenal glands via the blood stream and stimulate the release of cortisol, epinephrine, and norepinephrine. These neural and hormonal mechanisms mediate our responses to both ordinary stresses and intense stress.

at the base of the skull. ACTH travels to the adrenal glands via the blood stream and stimulate the release of cortisol, epinephrine, and norepinephrine. These neural and hormonal mechanisms mediate our responses to both ordinary stresses and intense stress.

|

"Richard Davidson, a neuroscientist at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, thinks he's found a connection in the brain that is especially important for resilience: the path from the prefrontal cortex-the seat of cognition and planning-to the amygdala, an emotional part of the brain that responds to threats. A stronger connection means the prefrontal cortex can more quickly tell the emotional amygdala to quiet down...." Excerpt from "Bounce Back" by Mandy Oaklander. TIme Magazine, Frontiers of Medicine, June 1, 2015 |

Types of Stress

- Normal Stress (Eustress) - An occurrence that causes a minimal amount of stress which passes quickly. It might provide a burst of energy that helps you get things done or a stimulus that helps you focus and improves your performance. Example: Athletes who are nervous before a competition can use their stress to sharpen their focus, enhance their alertness, and improve their performance.

- Distress - A more severe stress that causes significant disruption, but occurs for a relatively short period. The effects are significant, but temporary, and the individual typically returns to a normal state.. Example: A car crash in which the passenger suffers minor injuries.

- Traumatic Stress - The result of a profound event that alters one's beliefs and assumptions. Affected individuals recover over time, but they are forever changed. Stresses that are profound or unrelenting may exceed our capacity to cope, eventually causing fatigue, exhaustion, or breakdown. Example: A natural disaster or a major health diagnosis to oneself or a loved one.

One can also categorize stress based on its chronicity (from American Psychological Association: The Different Kinds of Stress).

Chronicity of Stress

- Acute Stress - The most common form of stress. It comes from demands and pressures of the recent past and anticipated demands and pressures of the near future. Acute stress is thrilling and exciting in small doses, but too much is exhausting. Example: A fast run down a challenging ski slope is exhilarating in the morning, but can become taxing and wearying later on in the day. Skiing beyond your limits can lead to falls and broken bones.

- Episodic Acute Stress - There are those, however, who suffer acute stress frequently, whose lives tend to be infused with chaos and crisis. They have many simultaneous demands of their time and attention and their inability to organize them leads to episodic acute stress. It is common for people with acute stress reactions to be over aroused, short-tempered, irritable, anxious, and tense. Often, they describe themselves as having a lot of nervous energy. They tend to always be in a rush, yet are always late. They tend to be abrupt and irritable. Interpersonal relationships deteriorate oftentimes because others tend to respond with hostility. Example: Those described as "Type As

" and 'worry warts

" and 'worry warts ' have characteristics that can create frequent episodes of acute stress.

' have characteristics that can create frequent episodes of acute stress. - Chronic Stress - The grinding stress that wears people down a little at a time over a long period of time. Chronic stress comes when a person cannot see a way out of a miserable situation. It can be unrelenting demands and pressures for seemingly interminable periods of time. Losing hope, the individual gives up searching for solutions. Some chronic stresses stem from traumatic, early childhood experiences that become internalized and remain painful and present. A view of the world or a belief system is created that perpetuates the unending stress (i.e., the world is a threatening place, you must be perfect at all times). The worst aspect of chronic stress is that people often get used to it. They may forget it is there. People are immediately aware of acute stress because it is new, yet they can ignore chronic stress because it is old, familiar, and sometimes, almost comfortable. Because physical and mental resources are depleted through long-term attrition, the symptoms of chronic stress are difficult to treat and may require extended medical as well as behavioral treatment and stress management. Example: The stress of poverty, being in a dysfunctional family situation, being trapped in a despised job or career.