Build Resilience and Cope with Stress

We all encounter stressful situations and events: death of a loved one, pressure at work or at school, serious illness or accidents, assaults, or any number of other traumatic events. While we all experience these difficult periods of life (sometimes very difficult), we generally find a way to get through them due to our resilience, which we can define simply as the ability to cope and to bounce back from stress and problems. The way that victims, spectators, care-givers, and resident responded to the Boston Marathon bombing is a high profile example of great resilience. We all experience stresses and trauma that can affect us individually and bring us to periods of worry, stress, and psychological pain. Getting beyond these problems involves resilience. Resilience does not mean avoided stress and adversity; it means have the ability to persevere and continue to function effectively despite failures, setbacks, and losses. This requires developing effective coping skills. People who are able to persist and continue to function at a high level in times of adversity generally have greater self-efficacy and less fear of failing.

Some people are more resilient than others, but resilience is not an innate trait that one is born with. It is a response that can be learned and nurtured, and there are some simple things that we can do to build our personal resilience. This brief module provides some insights and some evidence-based tips on how to build and nurture your resilience. These will not provide a way of avoiding the stresses and travails that are thrown in our path, but they will help you build the resilience to work through them to the other side.

This page is adapted from the module entitled "Dealing with Stress in Disasters" at the Local Public Health Institute of Massachusetts. (Link to the LPHI module)

This page is copied from the Local Public Health Institute of Massachusetts module at the following link: Link to Building Psychological Resilience for Dealing with Disasters.

Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines stress as: "a physical, chemical, or emotional factor that causes bodily or mental tension, and may be a factor in disease causation." If you were to ask people to explain what stress is and how it affects them, you would likely get a wide variety of definitions. Many factors and situations have the potential to impact us in stressful ways, but it is important to note our individual perceptions and responses to these stimuli.

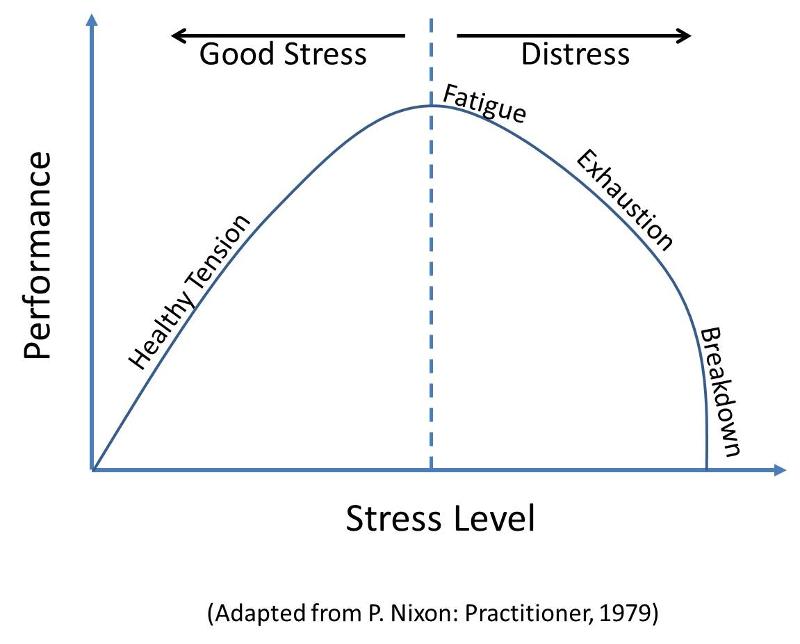

Athletes and performers often describe mental tension that arises prior to a contest or a performance, as anxiety or outright fear. Nevertheless, they acknowledge that this tension can both overwhelm the individual and result in a disastrous performance, or it can be the source of a positive response that brings out the very best in people. The graphic below attempts to illustrate both the potentially motivating effects of stress and the adverse effects of excessive or prolonged stress combined with poor coping skills (on the right).

Although we frequently have little control over stressful factors and situations, it is possible to train yourself to modulate your thoughts, emotions, and your environment in ways that help you to deal with the problems you encounter, rather than allowing events take control of you. Conceptually, your efforts to develop psychological resilience can expand your range of good stress and shrink the range of debilitating stress. This is what is meant by building psychological resilience, and it is particularly important for public health workers and emergency responders.

French physiologist Claude Bernard was the first to introduce the concept of dynamic equilibrium, or steady state. Organisms, even individual cells within organisms, are subject to never-ending changes in conditions. But in order to survive and maintain optimal function, built-in mechanisms respond to altered conditions (stresses) by making adjustments that are designed to re-establish equilibrium. As a simple example, if the external temperature rises, our bodies automatically perspire - a compensatory response that reduces our internal temperature.

Neurologist Walter Cannon applied the term homeostasis to this concept of dynamic equilibrium. Cannon was the first to propose that stressors could be emotional as well as physical, and he described the "fight or flight" response that occurs when animals are threatened with immediate danger (a severe stress). Hans Selye, another scientist, extended Cannon's observation and discovered that the "fight or flight" response is mediated by the secretion of powerful neurotransmitters. Stimuli from the brain also cause the hypothalamus to release corticotrophin releasing factor (CRF). CRF then causes the secretion of adrenocorticophic hormone (ACTH) from the pituitary gland at the base of the skull. ACTH travels to the adrenal glands via the blood stream and stimulate the release of cortisol, epinephrine, and norepinephrine. These neural and hormonal mechanisms mediate our responses to both ordinary stresses and intense stress.

|

"Richard Davidson, a neuroscientist at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, thinks he's found a connection in the brain that is especially important for resilience: the path from the prefrontal cortex-the seat of cognition and planning-to the amygdala, an emotional part of the brain that responds to threats. A stronger connection means the prefrontal cortex can more quickly tell the emotional amygdala to quiet down...." Excerpt from "Bounce Back" by Mandy Oaklander. TIme Magazine, Frontiers of Medicine, June 1, 2015 |

One can also categorize stress based on its chronicity (from American Psychological Association: The Different Kinds of Stress).

|

"Scientists can see how resilient brains respond to emotion differently, found Martin Paulus, scientific director and president of the Laureate Institute for Brain Research in Tulsa, Okla." "Paulus says that in his research he has seen differences in the brains of people with anxiety or depression that suggest they have a hard time letting go of emotions and are often too engaged in emotional processes." "And just like working your biceps or your abs, say experts, training your brain can build up strength in the right places-and at the right times-too." Excerpts from "Bounce Back" by Mandy Oaklander. TIme Magazine, Frontiers of Medicine, June 1, 2015

|

Taking care of your body is an important first step toward mental and emotional health. Below is a list of ways to improve your physical health:

|

"What's more, scientists have identified at least a dozen ways that people can up their resilience game, which Charney and Southwick detail in their 2012 book, Resilience: The Science of Mastering Life's Greatest Challenges, to be updated this year with reams of new research on the topic. 'For resilience, there's not one prescription that works,' Charney says. 'You have to find what works for you.' So far, researchers have found that facing the things that scare you relaxes the fear circuitry, making that a good first step in building resilience. They have also found that developing an ethical code to guide daily decisions can help. Studies have shown that traits scientists once thought of as nice but unnecessary-like having a strong network of social support-are critical to resilience." Excerpts from "Bounce Back" by Mandy Oaklander. TIme Magazine, Frontiers of Medicine, June 1, 2015 |

Many activities have been shown to reduce stress whether it involves team sports, group activities, or individual activity. Find a way to squeeze some regular activity into your day. Consider:

|

From: "Worried? You're Not Alone" by Roni Caryn Rabin, New York Times, May 9, 2016 Link to full article

...some coping strategies:

|

A personal support network is essential for building and maintaining your resilience. You need to build and maintain relationships with family members, friends, peers, and co-workers. Encouragement and support from these relationships is extremely effective in helping you work through stressful periods. Your peers can be a vitally important component of your support network, because they are likely to be experiencing similar stresses. Consequently, they are able to validate your feeling, empathize, and perhaps provide good advice as to how to deal with specific problems and situations.

You might consider establishing your own peer support groups in a way that is best suited to the time and space limitations of you and your peers.

The following information on Peer Support and Education is adapted from http://www.newhealthpartnerships.org

Today there are support groups for any number of things: caregivers, dieting, exercise, grief, illnesses, mental health, etc. What these groups have in common is that they consist of people who share a common experience. Peer support can be informal or more organized with regular meetings. The key thing is for the support group to focus on listening to and supporting one another and sharing information and advice.

Peer support helps in at least four ways.

And it is a two-way street, meaning that you provide support, advice, and information as well as receiving it. You can provide peer support as well as receive it.

The key skills to providing peer support are:

Certain feelings and behaviors signs indicating the need for prompt professional help. Important warning signs are:

If you feel that your resilience is crumbling, you should seek help without delay. And if you are unsure about what to do or where to seek help, you should contact the staff in Student Services, since they can connect you with appropriate professional help.