Ideas About Health

Systematic thinking about how to establish the determinants of health and disease was not suddenly invented by a single individual. It evolved over centuries. One can see sparks of insight intermittently over time. In the 1700s and 1800s one can see attempts to examine the causes of disease and the effectiveness of prevention and treatment in a systematic way. This page provides an interesting, but incomplete assortment of examples illustrating some of the major ideas that emerged and contributed to the evolution of how we investigate the factors associated with health and disease and establish the determinants.

Girolamo Fracastoro (1546)

Girolamo Fracastoro was an Italian physician, poet, astronomer, and geologist, who wrote about 'disease seeds' carried by wind or direct contact. In essence, he was proposing the germ theory of disease more than 300 years before its formal articulation by Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch.

In 1546, Fracastoro outlined his concept of epidemic diseases in "De contagione et contagiosis morbis" and speculated that each disease was caused by a different type of rapidly multiplying 'seed' and that these could be transmitted by direct contact, through the air, or on contaminated clothing and linens. Similar speculation had been mentioned as a possible cause of disease by the Roman scholar Marcus Varro in the 1st century BC.

It was once believed that life forms could arise spontaneously. Maggots, worms, & bacterial and fungal growth could be found "arising" from food that was left to stand. In 1699 Francesco Redi boiled broth and sealed it; no growth occurred, suggesting that Fracastoro was correct.

John Graunt - The Bills of Mortality (1662)

Beginning around 1592 the parish clerks in London began recording deaths. In 1662 John Graunt, a founding member of the Royal Society of London, summarized the data from these "Bills of Mortality" in a publication entitled "Natural and Political Observations Mentioned in a Following Index, and Made Upon the Bills of Mortality."

Graunt analyzed the data extensively and made a number of observations regarding common causes of death, higher death rates in men, seasonal variation in death rates, and the fact that some diseases had relatively constant death rates, while others varied considerably. Graunt also estimated population size and rates of population growth, and he was the first to construct a "life table" in order to address the issue of survival from the time of birth.

Anton van Leeuwenhouk (1670s)

Van Leeuwenhouk's accomplishments were preceded by those of Robert Hooke, who had published "Micrographia" in 1665. Hooke devised a compound microscope and used it to examine and describe the structure of nature on a microscopic level, including insects, feathers, and plants. In fact, it was Hooke who discovered plant cells and coined the term "cells".

Anton van Leeuwenhoek of Holland was "the father of microscopy." He began as an apprentice in a dry goods store where magnifying glasses were used to inspect the quality of cloth. Van Leeuwenhoek was fascinated by the lenses and experimented with new methods for grinding and polishing more powerful lenses.

He was able to achieve magnifications up to 270x diameters. He used these to create the first useful microscopes. Using his inventions, he was the first to see bacteria (1674), yeast, protozoa, sperm cells, and red blood cells.

John Pringle and "Jail Fever" (1740s)

John Pringle was a Scot who served as physician general to the British forces during the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–48). In London he became physician to the Duke of Cumberland and to King George III. Pringle published "Observations on the Diseases of the Army" in 1752, in which he proposed a number of measures aimed at improving the health of soldiers including improvements in hospital ventilation and camp sanitation, proper drainage, adequate latrines, and the avoidance of marshes.

He wrote extensively on the importance of hygiene to prevent typhus or "jail fever," which was a common malady among soldiers and prisoners in jails. Pringle incorrectly believed that typhus was caused by filth. In fact, it is caused by a small bacterium (a rickettsia). Lice are vectors for the disease; when infected lice defecate on the skin of lice-infested soldiers or prisoners, the bacteria can gain entry through small scratches or abrasions in the skin. The bacteria then multiply and cause a severe febrile illness which is often fatal if not treated. Pringle also coined the term 'influenza'.

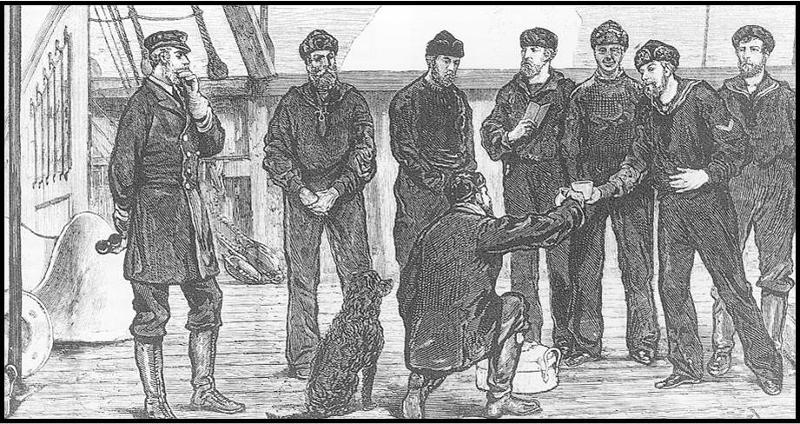

James Lind and Scurvy (1754)

Scurvy is due to a deficiency in vitamin C that results in weak connective tissue and abnormally fragile capillaries that rupture easily, causing bleeding, anemia, edema, jaundice, heart failure, and death. Scurvy was a huge problem in sailors several centuries ago, because of the chronic lack of fresh fruit and vegetables during long sea voyages. James Lind, a Scottish naval surgeon, suspected that citrus fruits could prevent it based on some anecdotal observations. In 1754 Lind conducted what may be the world's first controlled clinical trial on 12 sailors with scurvy.

Lind divided the 12 sailors into pairs, and each group received a different treatment (sea water, various other concoctions, and lemons and oranges. The two who received lemons and organs were cured, but the others were not. Lind concluded that his hypothesis was correct, reported his findings, and recommended that sailors receive a ration of lime or lemon juice.

Unfortunately, 50 years passed before the British navy acted on Lind's recommendations and began to provide lime juice to sailors at sea. (This led to the nickname "Limeys" for British sailors.) It is also noteworthy that Lind was able to correctly identify a means of preventing scurvy even though he misunderstood the cause. He believed toxins within the body were normally released through pores in the skin and that scurvy was the result of damp sea air causing pores to close, thus trapping toxins within the body.

Francois Broussais & Pierre Louis (1832)

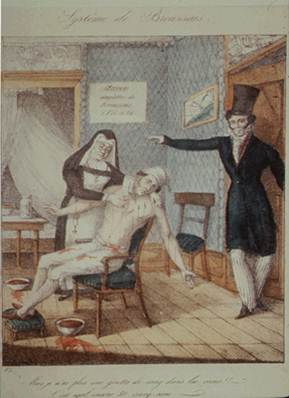

Bloodletting to Treat Cholera

Francois Broussais was a prominent Parisian physician and a strong proponent of bloodletting with leeches. He used bloodletting to treat many diseases, including cholera. In the engraving below Broussais can be seen instructing a nursing sister to continue to apply leeches to his patient (who is already quite pale from loss of blood). It is believed that his vigorous use of bloodletting to treat victims of a cholera epidemic in Paris substantially contributed to the mortality rate. The image below on the left is an engraving showing Broussais telling a nursing sister to continue bleeding has patient.

Pierre Louis was a contemporary of Broussais's who believed in using numerical methods to evaluate treatment. Louis studied bloodletting and found it ineffective, but many dismissed his conclusions. Bloodletting was a therapy that had been practiced for centuries, although it had never been tested for efficacy. It had become embedded in medical practice.