Follow Up in Cohort Studies

Selection bias from enrollment procedures rarely occurs in cohort studies, because the outcomes have not yet occurred at the time when subjects are enrolled, so a potential participant's eventual outcome status is unknown and therefore can not influence . However, selection bias can occur in a prospective cohort study as a result of differences in retention during the follow-up period after enrollment. When the observation period spans many years (in either retrospective or prospective cohort studies) it can be difficult to track subjects for the entire study. Subjects may disappear as a result of death, relocation, or (in prospective studies) loss of interest in the study. Studies with follow up rates of less than 60% will generally be seen as having limited validity, but even losses of 20% can introduce bias if the reasons for loss are related to both exposure status and outcome status.

Losses to follow-up can introduce bias (a deviation of the observed value of the measure of association from the value that would have been observed in the absence of bias) if there are differences in likelihood of loss to follow-up that are related to exposure status and outcome. In general, large prospective cohort studies are doing well if they can maintain follow-up of 80-90% of their sample for long periods.

Example:

As an illustration of how bias can be introduced with loss to follow-up, consider the following example. Suppose investigators were prospectively studying the association between use of oral contraceptives and development of thromboembolism (TE), i.e., blood clots in veins of the lower extremities or pelvis that can break loose and become lodged in the branches of the pulmonary artery]. Suppose, 20/10,000 OC users developed thromboembolism, but only 10/10,000 controls did, i.e., OC users really had a 2-fold greater risk. If roughly 4,000 subjects were lost to follow-up in each group, and if 12 of the 20 subjects who developed thromboembolism in the OC group became lost to follow-up, but only 2 subjects with thromboembolism were lost in the control group, the differential loss to follow-up would make it appear that rates of thromboembolism were similar, and the estimate of association (risk ratio) would be biased.The bias that can result from this differential follow up is a type of selection bias.

The enrollment of subjects in a prospective cohort study like this would not introduce selection bias, because the outcome has not yet occurred. However, retention of subjects may be differentially related to exposure and outcome, and this has a similar effect that can bias the results. In the hypothetical cohort study below investigators compared the incidence of thromboembolism (TE) in 10,000 women on oral contraceptives (OC) and 10,000 women not taking OC. TE occurred in 20 subjects taking OC and in 10 subjects not taking OC, so the true risk ratio was (20/10,000) / (10/10,000) = 2.

|

Unbiased Results |

Thromboembolism |

Non-diseased |

Totaal |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Oral Contraceptives |

20 |

9980 |

10,000 |

|

Unexposed |

10 |

9990 |

10,000 |

This unbiased data would give a risk ratio as follows:

However, suppose there were substantial loses to follow-up in both groups, and a greater tendency to loose subjects taking oral contraceptives who developed thromboembolism. In other words, there was differential loss to follow up with loss of 12 diseased subjects in the group taking oral contraceptives, but loss of only 2 subjects with thromboembolism in the unexposed group. This might result in a contingency table like the one shown below.

|

Biased Results |

Thromboembolism |

Non-diseased |

Totaal |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Oral Contraceptives |

8 |

5980 |

5988 |

|

Unexposed |

8 |

5984 |

5992 |

This biased data would give a risk ratio as follows:

So, in this scenario both exposure groups lost about 40% of their subjects during the follow up period, but there was a greater loss of diseased subjects in the exposed group than in the unexposed group, and it was this differential loss to followup that biased the results.

A study with substantial loss to follow does not have to produce a biased estimate of an association, but it certaintly raises concerns about the accuracy of the estimate. If the losses among the groups being compared are non-differntial, then the estimate will not be biased by the losses. Since there is no way of predictiing the effects of loss to follow up, researchers do their best to reduce it by maintaining contact with participants at regular intervals, collecting contact information from friends or relatives that would know how to reach a participant should s/he move, using the National Death Index and other databases to track the vital status of participants who do not respond to attempts at contact, as well as other strategies. Most of these strategies are only applicable to prospective cohort studies, because all the follow-up time has already occurred in a retrospective cohort study before the investigators get involved. Carefully done prospective cohort studies will go to extraordinary lengths to maintain high follow-up rates.

|

|

Unlike the bias that can occur from differential loss to follow up, selection bias at enrollment rarely occurs in cohort studies, because the outcomes have not yet occurred at the time when subjects are enrolled, so a potential participant's eventual outcome status is unknown and therefore can not influence their participation. This is even more unlikely in prospective than retrospective cohort studies, although even in the latter the cohort is almost always created based on information that was recorded prior to the development of the outcome.

Non-participation in a Prospective Cohort Study

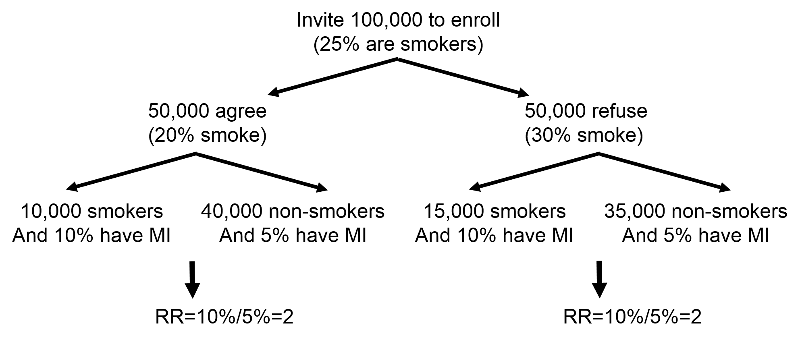

Ordinarily, some of the individuals invited to be subjects in a prospective cohort study refuse to participate. This can produce bias in retrospective cohort studies and case-control studies, because exposure status and outcomes have already occurred at the time of enrollment. However, non-participations will not bias a prospective cohort study in which the outcomes of interest have not yet occurred. To illustrate suppose 100,000 subjects are invited to be in a study on the association between smoking and risk of heart attack, but 50,000 refuse to participate. Only 20% of those who agree are smokers versus 30% in those who refuse. The frequency of smoking in the study subjects is not representative of its prevalence in the population, but you can still compare smokers and non-smokers with respect to the incidence of myocardial infarction. In a situation like this, substantial non-participation could detract from the generalizability of the findings. For example, if there were a high rate of non-participation among African-Americans, it might not be appropriate to extrapolate the findings to this subset of the population.

Selection Bias in Retrospective Cohort Studies

A similar type of bias can occur in retrospective cohort studies if subjects in one of the exposure groups are more or less likely to be selected if they had the outcome of interest.

Example:

Consider a hypothetical investigation of an occupational exposure (e.g., an organic solvent) that occurred 15-20 years ago in factory. Over the years there were suspicions that working eith the solvent led to adverse health events, but no definitive data existed. Eventually, a retrospective cohort study was conducted using the employee health records. If all records had been retained the results might have looked like those shown in the first contingency table below.

|

Unbiased Results |

Diseased |

Non-diseased |

Totaal |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Solvent exposure |

100 |

900 |

1000 |

|

Unexposed |

50 |

950 |

1000 |

This unbiased data would give a risk ratio as follows:

However, suppose that many of the old records had been lost or discarded, but,given the suspicions about the effects of the solvent, the records of employees who had worked with the solvents and subequently had health problems were more likely to be retained. Consequently, record retention was 99% among workers who were exposed and developed health problems, but recorded retention was only 80% for all other workers. This scenario would result in data shown in the next contingency table.

|

Biased Results |

Diseased |

Non-diseased |

Totaal |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Solvent exposure |

99 |

720 |

819 |

|

Unexposed |

40 |

760 |

800 |

Differential loss of records results in selection bias and an overestimate of the association in this case, although depending on the scenario, this type of selection bias could also result in an underestimate of an associaton.

|

|