Transition to Cancer in a Single Cell

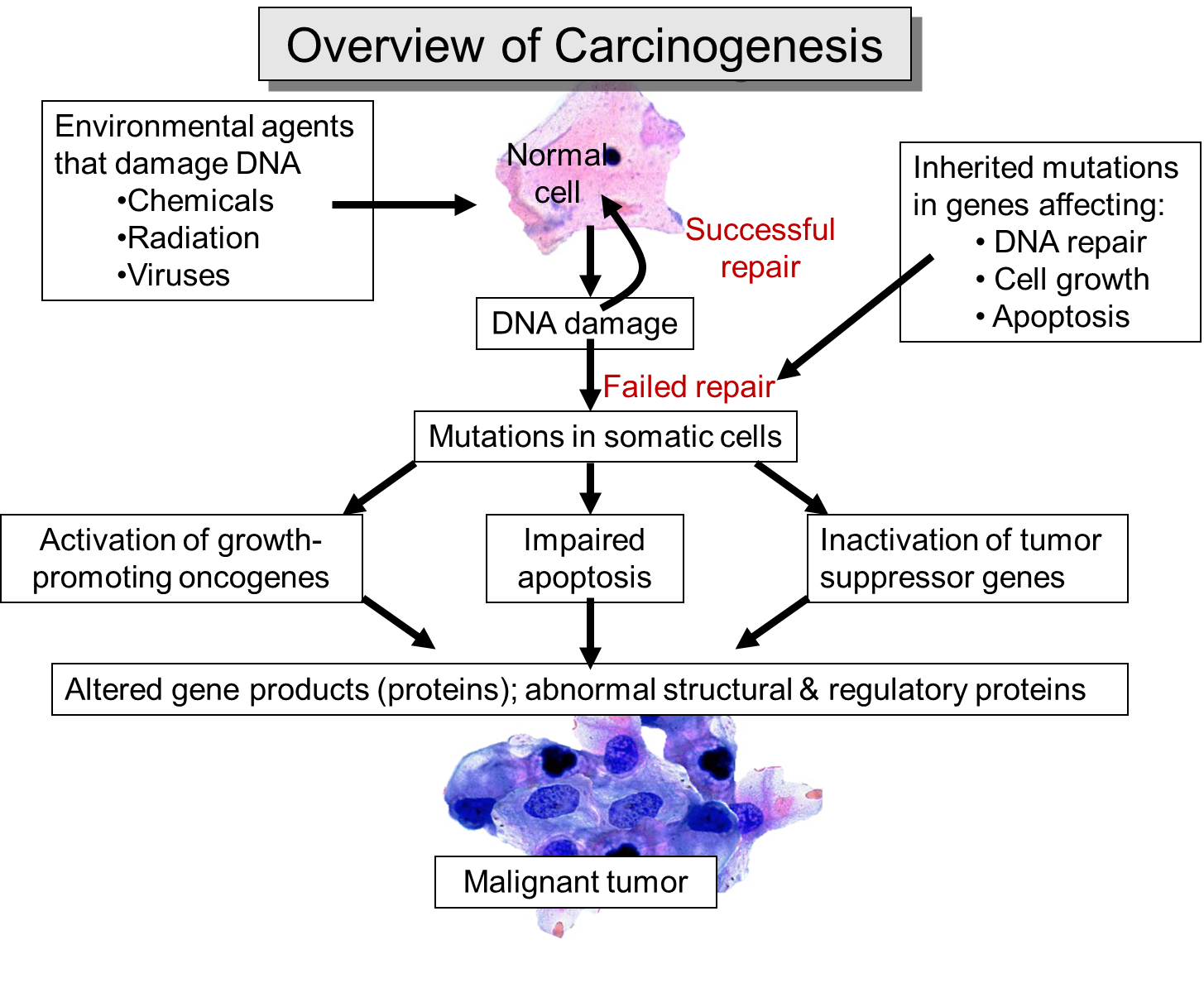

Cancer is a clonal disease, meaning that accumulated mutations in a single cell lead to unregulated proliferation, a loss of differentiation, and abnormal behavior. With unregulated proliferation, a single cell will give rise to an ever increasing clone of similarly abnormal cells, although the progeny cells may acquire still more mutations over time. The gene abnormalities (mutations) may be inherited (for example, defective Rb in the familial form of retinoblastoma) or they may be acquired as a result of viral infection or damage to cellular DNA caused by carcinogens, e.g., chemicals in cigarette smoke, asbestos, radiation (UV, radon gas, X-rays). It is also possible for mutations to occur as random errors during cell division. There are cellular mechanisms that repair defects in DNA, but repair is not always successful.

What Is a Carcinogen?

In the short video clip below Dr. David Sherr, from the environmental health department at BUSPH explains what a carcinogen is.

Defects in DNA Repair

The preceding pages make it clear that cancer evolves as the result of an accumulation of mutations within a single cell. Cells have enzymes whose function is to repair defects in DNA. The genes that encode for these enzyme repair mechanism can also be damaged by mutations. In addition, there are several inherited defects in DNA repair that increase the likelihood of transition to malignancy. For example, xeroderma pigmentosum is an inherited defect in DNA repair that causes extreme sensitivity to ultraviolet light, making them extremely vulnerable to sunburn and skin cancers. Ultraviolet light penetrates the superficial layers of the skin, and causes damage to DNA when the radiant energy is absorbed. For more information on ultraviolet light and adverse effects of overexposure see the module on Sun Exposure.