Early Concepts of Disease

Hunter-Gatherers:

Ten thousand years ago humans were hunter-gatherers. They had a short life span, but not because of epidemics; their primary problem was just finding enough food to eat. They lived and traveled in small groups and hunted and foraged for food. Their mixed diet was probably fairly balanced and nutritionally complete. Since they lived in small groups and moved frequently, they had few problems with accumulating waste or contaminated water or food.

Mythology, Superstition, and Religion

Early explanations for the occurrence of disease focused on superstition, myths, and religion. Primitive peoples believed in natural spirits that were sometimes mischievous or vengeful. The Greeks believed that the god Jupiter was angry about man accepting the gift of fire. The story is long and complicated, but Zeus crammed all the diseases, sorrows, vices, and crimes that afflict humanity into a box and gave it to Epimetheus, the husband of Pandora. Mercury was very tired from carrying his burden and gave it to Epimetheus for safe keeping. Pandora wanted desperately to know what was in the box. She waited until Epimetheus was gone. She opened the box, and all of the ills of the world flew out and spread throughout the human world.

Link to more on the myth of Pandor'a box

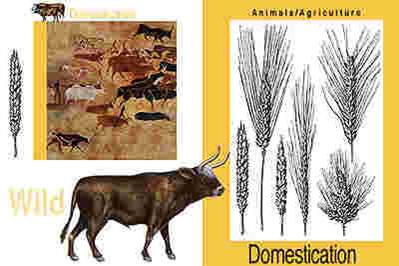

The Agricultural Revolution

The shift from the hunter-gather mode of living to an agricultural model provided a more secure supply of food and enabled expansion of the population. However, domesticated animals provided not only food and labor; they also carried diseases that could be transmitted to humans. People also began to rely heavily on one or two crops, so their diets were often lacking in protein, minerals , and vitamins

, and vitamins . People began living in larger groups and staying in the same place, so there was more opportunity for transmission of diseases.

. People began living in larger groups and staying in the same place, so there was more opportunity for transmission of diseases.

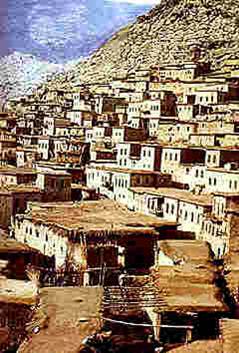

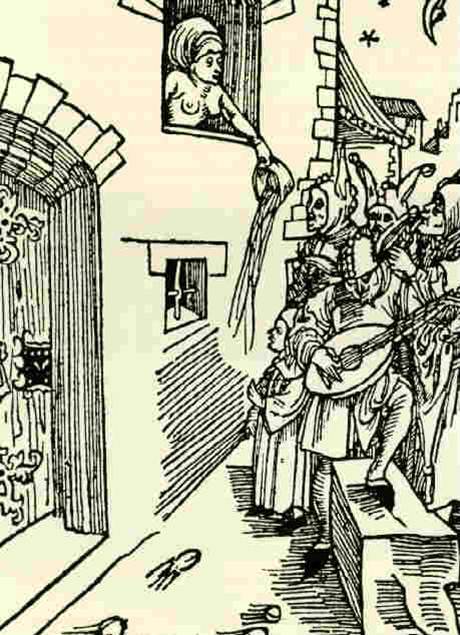

The image on the left below shows one of the primitive, but enormously overcrowded communities that evolved after the agricultural revolution. Dense populations like this often had inadequate means of disposing of garbage and sewage, which tended to accumulate. Rodents and insect vectors were attracted to human settlements, providing a means of spreading disease. The engraving on the right shows a woman in a medieval town emptying her bedpan into the street.

were attracted to human settlements, providing a means of spreading disease. The engraving on the right shows a woman in a medieval town emptying her bedpan into the street.

The Hippocratic Corpus

For many centuries explanations for disease were based not on science, but on religion, superstition, and myth.

The Hippocratic Corpus was an early attempt to think about diseases, not as punishment from the gods, but as an imbalance of man with the environment. (Link to more information on the Hippocratic Corpus) Although it was unsophisticated by today's standards, it was an important step forward. By considering the possibility that disease was associated with environmental factors or imbalances in diet or personal behaviors, the Corpus also opened up the possibility of intervening to prevent disease or treat it.

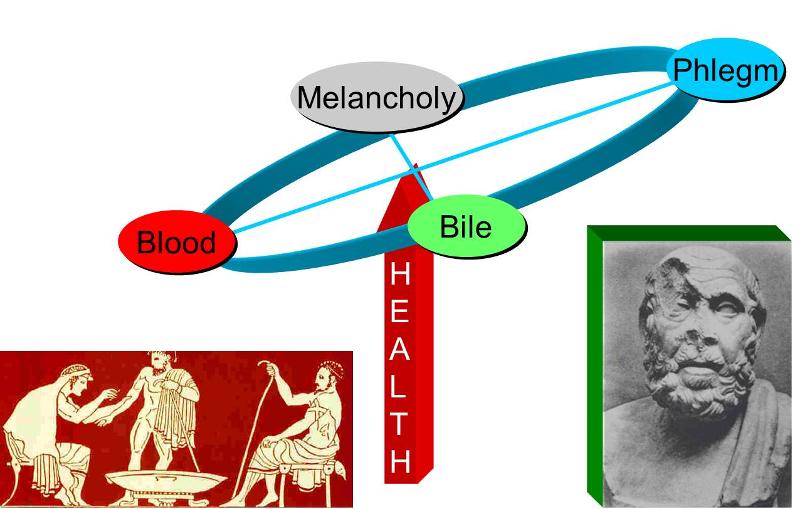

The Corpus looked at disease as an imbalance in natural forces or an imbalance in humours (or fluids): melancholy, phlegm, bile, and blood. Health depended on a proper balance of these humours. While crude, this concept of humours provided some sort of rationale for understanding health and disease. Greek physicians prescribed changes in diet or lifestyle and sometimes concocted drugs or performed surgery. An excess of the humour blood, for example, became the rationale for bloodletting, a practice that was followed for centuries without any evidence of its efficacy. (Link to more information on bloodletting)

Despite the contributions of the Corpus, medical and scientific progress in Europe was arrested for several centuries. The population grew, and cities became densely populated, but there was little attention to waste disposal and sanitation. These factors set the stage for endemic disease and periodic epidemics.

The Bubonic Plague

Bubonic plague is an acute infectious disease caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis. The bacteria live in the intestines of fleas and are transmitted to rats by flea bites. The rats, therefore, serve as a natural reservoir for the disease, and fleas are the vectors. Occasionally, an infected flea would jump to a human and introduce the bacteria when a blood meal was taken. The bacteria would then spread to the regional lymph nodes and multiply, causing dark, tender, swollen nodules (buboes), as shown to the right. As the infection spread, the victim would experience headache, high fever, delirium, and finally death in about 60% of cases.

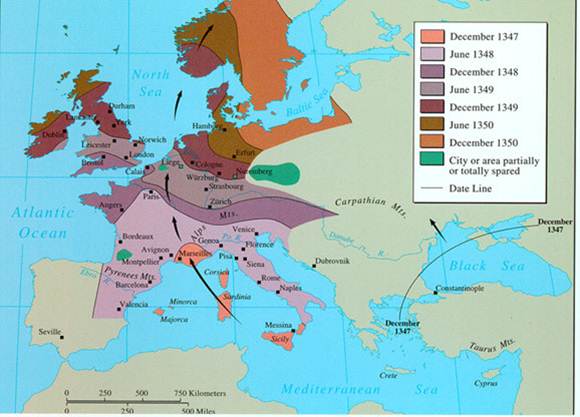

Starting in 1347, Europe experienced multiple waves of bubonic plague epidemics that lasted until the late 1700s. It is believed that the bubonic plague originated in Asia and traveled along trade routes into the Black Sea and then into the Mediterranean Sea. From there, it swept through Sicily and Italy and then up through France and the northern European countries all the way up into Scandinavia. There were many subsequent waves of plague that swept through Europe until the late 1700s. The map below shows the spread of plague over a three year period from Asia across the Black Sea into the Mediterranean and then through Italy, France, England, Northern Europe, and into Scandinavia. (Link to more on the bubonic plague)

Cause of the Plague and Strategies for Prevention

The cause of the plague was not known, but there were many theories. The most popular explanation was that it was caused by "miasmas," invisible vapors that emanated from swamps or cesspools and floated around in the air, where they could be inhaled. Others thought it was spread by person to person contact, or perhaps by too much sun exposure, or by intentional poisoning. The miasma theory was the most popular, however. One of the popes kept large fires burning at both ends of the room he worked in order to counteract the miasmas.

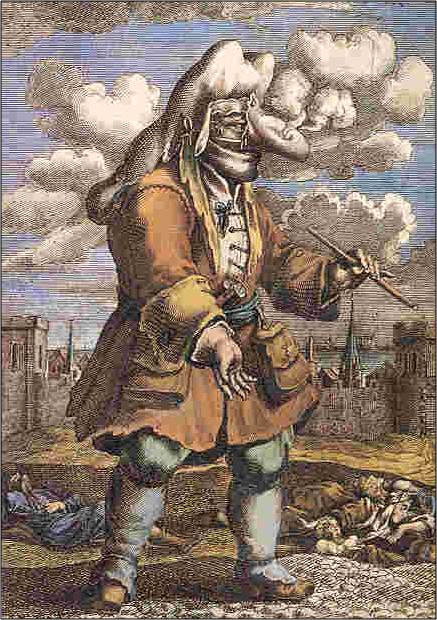

There were also crude medicines that were concocted to prevent or cure the bubonic plague; one of them was known as theriac . Of course, smoke and aromatic herbs and theriac were ineffective, because the plague was primarily spread by flea bites (although sometimes victims developed a plague pneumonia that caused them to cough up a bloody, plague-filled aerosol that could be transmitted to others by inhalation; this was the 'pneumonic' form of the plague). The illustration below shows one of the "plague doctors" who were clothed from head to toe (including hood and mask) in order to protect themselves from the miasmas that spread plague.

. Of course, smoke and aromatic herbs and theriac were ineffective, because the plague was primarily spread by flea bites (although sometimes victims developed a plague pneumonia that caused them to cough up a bloody, plague-filled aerosol that could be transmitted to others by inhalation; this was the 'pneumonic' form of the plague). The illustration below shows one of the "plague doctors" who were clothed from head to toe (including hood and mask) in order to protect themselves from the miasmas that spread plague.

While most believed that plague was caused by miasmas, the primary mode of transmission was actually via flea bites, and, in a sense, the real causes were increased population density and failure to dispose of garbage. Accumulations of garbage attracted rats and enabled the rat population to explode. Rats had harbored fleas and Yersinia pestis for many years without major difficulty, and plague epidemics in humans didn't occur until human behaviors created environments that brought people into proximity with rats, fleas, and Yersina pestis. These were the real causes of the plague epidemics.

At first glance one might blame the lack of understanding about transmission and the ineffective preventive measures on the primitive level of scientific understanding. However, the inability to identify the cause and the inability to identify effective control measures was not due to a lack of sophisticated technology. Instead, it was primarily due to the fact that humans had not yet developed a structured way to think about the determinants of disease. There were certainly theories of how the plague spread and these led to preventive strategies, but none of the theories or preventive strategies or treatments were ever tested by collecting observations in groups of people. The idea of studying groups of people to test associations between "risk factors" and disease outcomes had not yet evolved.

|

Key Concept: The lack of a systematic way of testing possible associations between exposures and outcomes ("risk factors" and disease) was the major factor that prevented advances in understanding the causes of disease and the development of effective strategies to prevent or treat disease.

|

Quarantine and Isolation

The use of quarantine as a public health measure dates back to the 14th century when the Black Death ravaged Italy and the rest of Europe. Quarantine comes from the Italian quarantena, meaning forty-day period. Travelers and merchandise that had potentially been exposed to disease were isolated for a period of time to ensure that they weren't infected. Some cities and towns would create a "cordon sanitaire,' a physical barrier that could only be crossed with permission. This practice persisted into the late 19th century and early 20th century. When plague threatened San Francisco, the Chinese section was quarantined by encircling it with a rope with armed guards to ensure that unauthorized individuals did not pass through. a "cordon sanitaire" was also used during an outbreak of bubonic plague in 1899-1900 in Honolulu's Chinatown. Fourteen blocks of the city were literally cordoned off, isolation 10,000 people..

While quarantine is one of the oldest public health measures, it is still useful today. During the SARS epidemic, Toronto quarantined individuals who had potentially been exposed by confining them to their homes until it was certain that they weren't infected. This measure was effective in controlling SARS because individuals infected with SARS were not infectious until they began to exhibit symptoms. Consequently, if an individual was possibly exposed, but did not yet show symptoms, quarantine prevented them from infecting others. However, quarantine is less useful for diseases like influenza, when an infected person can spread the disease even before they begin having symptoms. Quarantine is different from isolation, which is separation of a person who has the disease; quarantine refers to the separation of an individual who has possibly been exposed to disease.

Video: The Past, Present and Future of the Bubonic Plague - Sharon N. DeWitte (from www.TED.com)