Selecting & Defining Cases and Controls

The "Case" Definition

Careful thought should be given to the case definition to be used. If the definition is too broad or vague, it is easier to capture people with the outcome of interest, but a loose case definition will also capture people who do not have the disease. On the other hand, an overly restrictive case definition is employed, fewer cases will be captured, and the sample size may be limited. Investigators frequently wrestle with this problem during outbreak investigations. Initially, they will often use a somewhat broad definition in order to identify potential cases. However, as an outbreak investigation progresses, there is a tendency to narrow the case definition to make it more precise and specific, for example by requiring confirmation of the diagnosis by laboratory testing. In general, investigators conducting case-control studies should thoughtfully construct a definition that is as clear and specific as possible without being overly restrictive.

Investigators studying chronic diseases generally prefer newly diagnosed cases, because they tend to be more motivated to participate, may remember relevant exposures more accurately, and because it avoids complicating factors related to selection of longer duration (i.e., prevalent) cases. However, it is sometimes impossible to have an adequate sample size if only recent cases are enrolled.

Sources of Cases

Typical sources for cases include:

- Patient rosters at medical facilities

- Death certificates

- Disease registries (e.g., cancer or birth defect registries; the SEER Program [Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results] is a federally funded program that identifies newly diagnosed cases of cancer in population-based registries across the US )

- Cross-sectional surveys (e.g., NHANES, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey)

Selection of the Controls

As noted above, it is always useful to think of a case-control study as being nested within some sort of a cohort, i.e., a source population that produced the cases that were identified and enrolled. In view of this there are two key principles that should be followed in selecting controls:

- The comparison group ("controls") should be representative of the source population that produced the cases.

- The "controls" must be sampled in a way that is independent of the exposure, meaning that their selection should not be more (or less) likely if they have the exposure of interest.

If either of these principles are not adhered to, selection bias can result (as discussed in detail in the module on Bias).

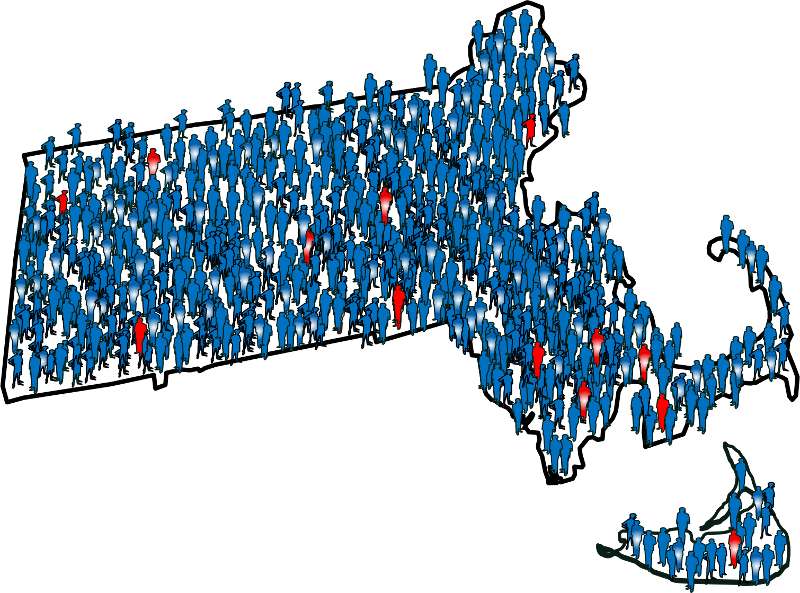

Note that in the earlier example of a case-control study conducted in the Massachusetts population, we specified that our sampling method was random so that exposed and unexposed members of the population had an equal chance of being selected. Therefore, we would expect that about 1,000 would be exposed and 5,000 unexposed (the same ratio as in the whole population), and came up with an odds ratio that was same as the hypothetical risk ratio we would have had if we had collected exposure information from the whole population of six million:

What if we had instead been more likely to sample those who were exposed, so that we instead found 1,500 exposed and 4,500 unexposed among the 6,000 controls? Then the odds ratio would have been:

This odds ratio is biased because it differs from the true odds ratio. In this case, the bias stemmed from the fact that we violated the second principle in selection of controls. Depending on which category is over or under-sampled, this type of bias can result in either an underestimate or an overestimate of the true association.

Example:

A hypothetical case-control study was conducted to determine whether lower socioeconomic status (the exposure) is associated with a higher risk of cervical cancer (the outcome). The "cases" consisted of 250 women with cervical cancer who were referred to Massachusetts General Hospital for treatment for cervical cancer. They were referred from all over the state. The cases were asked a series of questions relating to socioeconomic status (household income, employment, education, etc.). The investigators identified control subjects by going door-to-door in the community around MGH from 9:00 AM to 5:00 PM. Many residents are not home, but they persist and eventually enroll enough controls. The problem is that the controls were selected by a different mechanism than the cases, AND the selection mechanism may have tended to select individuals of different socioeconomic status, since women who were at home may have been somewhat more likely to be unemployed. In other words, the controls were more likely to be enrolled (selected) if they had the exposure of interest (lower socioeconomic status).