Case-Control Studies

Cohort studies have an intuitive logic to them, but they can be very problematic when:

- The outcomes being investigated are rare;

- There is a long time period between the exposure of interest and the development of the disease; or

- It is expensive or very difficult to obtain exposure information from a cohort.

In the first case, the rarity of the disease requires enrollment of very large numbers of people. In the second case, the long period of follow-up requires efforts to keep contact with and collect outcome information from individuals. In all three situations, cost and feasibility become an important concern.

A case-control design offers an alternative that is much more efficient. The goal of a case-control study is the same as that of cohort studies, i.e. to estimate the magnitude of association between an exposure and an outcome. However, case-control studies employ a different sampling strategy that gives them greater efficiency. As with a cohort study, a case-control study attempts to identify all people who have developed the disease of interest in the defined population. This is not because they are inherently more important to estimating an association, but because they are almost always rarer than non-diseased individuals, and one of the requirements of accurate estimation of the association is that there are reasonable numbers of people in both the numerators (cases) and denominators (people or person-time) in the measures of disease frequency for both exposed and reference groups. However, because most of the denominator is made up of people who do not develop disease, the case-control design avoids the need to collect information on the entire population by selecting a sample of the underlying population.

Rothman describes the case-control strategy as follows:

describes the case-control strategy as follows:

|

"Case-control studies are best understood by considering as the starting point a source population, which represents a hypothetical study population in which a cohort study might have been conducted. The source population is the population that gives rise to the cases included in the study. If a cohort study were undertaken, we would define the exposed and unexposed cohorts (or several cohorts) and from these populations obtain denominators for the incidence rates or risks that would be calculated for each cohort. We would then identify the number of cases occurring in each cohort and calculate the risk or incidence rate for each. In a case-control study the same cases are identified and classified as to whether they belong to the exposed or unexposed cohort. Instead of obtaining the denominators for the rates or risks, however, a control group is sampled from the entire source population that gives rise to the cases. Individuals in the control group are then classified into exposed and unexposed categories. The purpose of the control group is to determine the relative size of the exposed and unexposed components of the source population." |

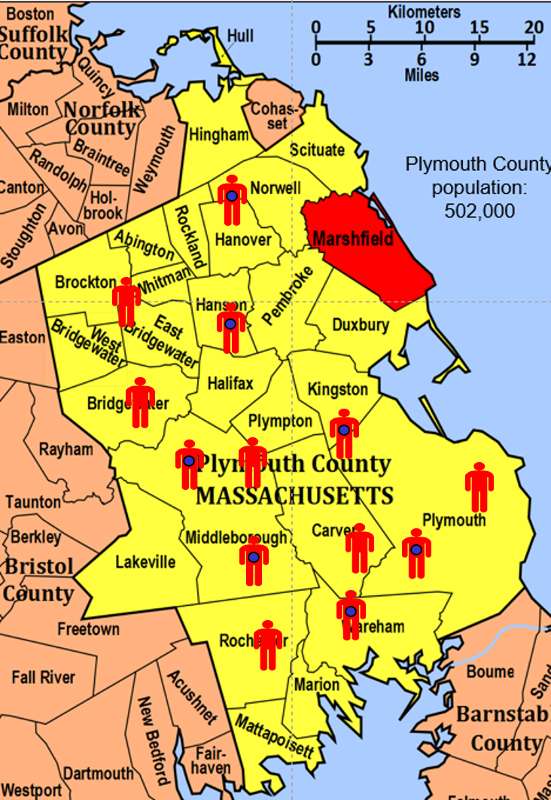

To illustrate this consider the following hypothetical scenario in which the source population is Plymouth County in Massachusetts, which has a total population of 6,647 (hypothetical). Thirteen people in the county have been diagnosed with an unusual disease and seven of them have a particular exposure that is suspected of being an important contributing factor. The chief problem here is that the disease is quite rare.

If I somehow had exposure and outcome information on all of the subjects in the source population and looked at the association using a cohort design, it might look like this:

|

|

Diseased |

Non-diseased |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Exposed |

7 |

1,000 |

1,007 |

|

Non-exposed |

6 |

5,634 |

5,640 |

Therefore, the incidence in the exposed individuals would be 7/1,007 = 0.70%, and the incidence in the non-exposed individuals would be 6/5,640 = 0.11%. Consequently, the risk ratio would be 0.70/0.11=6.52, suggesting that those who had the risk factor (exposure) had 6.5 times the risk of getting the disease compared to those without the risk factor. This is a strong association.

In this hypothetical example, I had data on all 6,647 people in the source population, and I could compute the probability of disease (i.e., the risk or incidence) in both the exposed group and the non-exposed group, because I had the denominators for both the exposed and non-exposed groups.

The problem, of course, is that I usually don't have the resources to get the data on all subjects in the population. If I took a random sample of even 5-10% of the population, I might not have any diseased people in my sample.

An alternative approach would be to use surveillance databases or administrative databases to find most or all 13 of the cases in the source population and determine their exposure status. However, instead of enrolling all of the other 5,634 residents, suppose I were to just take a sample of the non-diseased population. In fact, suppose I only took a sample of 1% of the non-diseased people and I then determined their exposure status. The data might look something like this:

|

|

Diseased |

Non-diseased |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Exposed |

7 |

10 |

unknown |

|

Non-exposed |

6 |

56 |

unknown |

With this sampling approach I can no longer compute the probability of disease in each exposure group, because I no longer have the denominators in the last column. In other words, I don't know the exposure distribution for the entire source population. However, the small control sample of non-diseased subjects gives me a way to estimate the exposure distribution in the source population. So, I can't compute the probability of disease in each exposure group, but I can compute the odds of disease in the case-control sample.

The Odds Ratio

The odds of disease among the exposed sample are 7/10, and the odds of disease in the non-exposed sample are 6/56. If I compute the odds ratio, I get (7/10) / (5/56) = 6.56, very close to the risk ratio that I computed from data for the entire population. We will consider odds ratios and case-control studies in much greater depth in a later module. However, for the time being the key things to remember are that:

- The sampling strategy for a case-control study is very different from that of cohort studies, despite the fact that both have the goal of estimating the magnitude of association between the exposure and the outcome.

- In a case-control study there is no "follow-up" period. One starts by identifying diseased subjects and determines their exposure distribution; one then takes a sample of the source population that produced those cases in order to estimate the exposure distribution in the overall source population that produced the cases. [In cohort studies none of the subjects have the outcome at the beginning of the follow-up period.]

- In a case-control study, you cannot measure incidence, because you start with diseased people and non-diseased people, so you cannot calculate relative risk.

- The case-control design is very efficient. In the example above the case-control study of only 79 subjects produced an odds ratio (6.56) that was a very close approximation to the risk ratio (6.52) that was obtained from the data in the entire population.

- Case-control studies are particularly useful when the outcome is rare is uncommon in both exposed and non-exposed people.

The Difference Between "Probability" and "Odds"?

- The probability that an event will occur is the fraction of times you expect to see that event in many trials.

Probabilities always range between 0 and 1.

Probabilities always range between 0 and 1. - The odds are defined as the probability that the event will occur divided by the probability that the event will not occur.

If the probability of an event occurring is Y, then the probability of the event not occurring is 1-Y. (Example: If the probability of an event is 0.80 (80%), then the probability that the event will not occur is 1-0.80 = 0.20, or 20%.

The odds of an event represent the ratio of the (probability that the event will occur) / (probability that the event will not occur). This could be expressed as follows:

Odds of event = Y / (1-Y)

So, in this example, if the probability of the event occurring = 0.80, then the odds are 0.80 / (1-0.80) = 0.80/0.20 = 4 (i.e., 4 to 1).

- If a race horse runs 100 races and wins 25 times and loses the other 75 times, the probability of winning is 25/100 = 0.25 or 25%, but the odds of the horse winning are 25/75 = 0.333 or 1 win to 3 loses.

- If the horse runs 100 races and wins 5 and loses the other 95 times, the probability of winning is 0.05 or 5%, and the odds of the horse winning are 5/95 = 0.0526.

- If the horse runs 100 races and wins 50, the probability of winning is 50/100 = 0.50 or 50%, and the odds of winning are 50/50 = 1 (even odds).

- If the horse runs 100 races and wins 80, the probability of winning is 80/100 = 0.80 or 80%, and the odds of winning are 80/20 = 4 to 1.

NOTE that when the probability is low, the odds and the probability are very similar.

On Sept. 8, 2011 the New York Times ran an article on the economy in which the writer began by saying "If history is a guide, the odds that the American economy is falling into a double-dip recession have risen sharply in recent weeks and may even have reached 50 percent." Further down in the article the author quoted the economist who had been interviewed for the story. What the economist had actually said was, "Whether we reach the technical definition [of a double-dip recession] I think is probably close to 50-50."

Question: Was the author correct in saying that the "odds" of a double-dip recession may have reached 50 percent?

|

Key Concept: In a study that is designed and conducted as a case-control study, you cannot calculate incidence. Therefore, you cannot calculate risk ratio or risk difference. You can only calculate an odds ratio. However, in certain situations a case-control study is the only feasible study design. |