Cultural Awareness

Reflections, Videos & Vignettes to Promote Cultural Awareness

Welcome!

An understanding of your culture and a recognition and acceptance of other cultures is an important component of your success as a public health practitioner.

In creating this module we sought help from faculty members, staff members, and students who have had significant experience in working on health initiatives overseas. Every person's experience will be unique. This introduction to cultural competencies is meant to help make you more aware of the lens through which you view your own culture and those of others.

Let's first introduce our panelists.

After completing this module, students should be able to:

|

"Culture is the acquired knowledge people use to interpret experience and generate behavior." - James Spradley, Anthropologist

|

An understanding of culture requires an understanding not only of language differences, but also differences in knowledge, perceptions, beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors.

Culture (from the Latin cultura stemming from colere, meaning "to cultivate") generally refers to patterns of human activity and the symbolic structures that give such activities significance and importance. Cultures can be "understood as systems of symbols and meanings that even their creators contest, that lack fixed boundaries, that are constantly in flux, and that interact and compete with one another."

Culture can be defined as all the ways of life including arts, beliefs and institutions of a population that are passed down from generation to generation. Culture has been called "the way of life for an entire society." As such, it includes codes of manners, dress, language, religion, rituals, art. norms of behavior, such as law and morality, and systems of belief.

Let's listen to the thoughts of our panelists.

Culture is in some ways like an iceberg. Just as an iceberg has a visible section above the waterline and a larger, invisible section below the water line, so culture has some aspects that are easily seen and others that are very subtle and difficult to see and understand. Also like an iceberg, that part of culture that is visible (observable behavior) is only a small part of a much bigger whole.

In the activity below the red cards describe various features of culture. Place each of these items in one of the two categories provided.

How do you define American culture?

Are the images below consistent with your notion of American culture?

|

Home made apple pie "As American as apple pie" |

A cowboy on the American frontier. Many have considered America as a land of unlimited resources and possibilities. There is a characteristic "rugged individualism" and a belief that you can do anything you put your mind to it. |

The Statue of Liberty Symbolizing freedom, democracy, International friendship, & opportunity, "Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to be free." |

|

The scales of justice All men and women are created and should be treated equal. There is rule of law, and a system of checks and balances |

Celebrities There is an obsession with the rich and famous. Actors and athletes are idolized by many. And many have a constant desire to have more. |

Baseball

An "all American" game symbolizing fun, competition, and a carefree attitude, |

Wikipedia breaks "culture of the United States" up into various categories including literature, television, dance, visual arts, theater, cuisine, fashion and popular culture. What does the term American culture mean to you? When you Google "American culture" some interesting links come up, if you would like to see how some other people define it, click on the following links: http://www.zompist.com/amercult.html

The table below lists some specific aspects of culture and typical American beliefs or sayings for each. You may not personally agree with these beliefs, but they portray the image that people in other cultures have of Americans. The last column provides a comment on each

As you read through this section think about any similarities or differences between the typical American view of these things and the possible views of people in other cultures.

|

Aspect |

Beliefs and Sayings |

Comments |

|

Age |

It's good to be young. · Out with the old in with the new. |

Comment |

|

Fate and Destiny |

Where there's a will there's a way. You can be whatever you want. |

Comment |

|

Human Nature |

You're innocent until proven guilty. Give the benefit of the doubt. |

Comment |

|

Change |

New is better. · Just because we've always done it that way doesn't make it right. |

Comment |

|

Risk Taking |

You can always start over. Nothing ventured, nothing gained. |

Comment |

|

Suffering and Misfortune |

If you're unhappy, take a pill or see a psychiatrist · Don't worry; be happy. |

Comment |

|

Self-esteem and Self-worth |

Material possessions are a measure of success. "Nice to meet you, What do you do?" |

Comment |

|

Equality |

Everyone deserves to be treated equally. Putting on airs is frowned upon. |

Comment |

|

Reality |

Bad things happen for a reason. It can't get any worse. |

Comment |

|

Getting Things Done |

Be practical. Actions speak louder than words. |

Comment |

The essence of cross-cultural understanding is knowing how your own culture is both similar to and different from other cultures. For this reason, those who pursue cross-cultural knowledge must sooner or later turn their gaze on themselves. People from other cultures, after all, aren't different by definition, but only different in relation to a particular standard they're being measured against. To even see those differences, therefore, you have to examine that standard. You might wonder why people from the United States would need to have their culture revealed to them. Isn't American culture obvious? However, the fact is that people from a given culture are in many ways the least able to see it. They embody the culture, of course, but they have to get out of that body if they wanted to see what it looks like.

No one American is quite like any other American, but a handful of core values and beliefs do underlie and permeate the national culture. These values and beliefs don't apply across the board in every situation, and we may, on occasion, even act in ways that directly contradict or flaunt them, but they are still at the heart of our cultural ethos.

In the iceberg exercise, you saw how certain aspects or features of culture are visible-- they show up in people's behavior--while many other aspects of culture are invisible, existing only in the realms of thought, feeling, and belief. The examples in this exercise show how these two realms, the visible and the hidden, are related to each other, how the values and beliefs you cannot see affect behavior. To understand where behavior comes from - to understand why people behave the way they do - requires learning about values and beliefs. While the behavior of people from another culture may seem strange to you, it probably makes sense to them. The reason any behavior makes sense is simply because it is consistent with what a given person believes in or holds dear. Conversely, when we say that what someone has done "makes no sense," what we mean is that that action contradicts what we know that person feels or wants.

In the exercise below, match the behavior to the value or belief that it exemplifies.

Culture is but one category or dimension of human behavior, and it is therefore important to see it in relation to the other two dimensions: the universal and the personal. The three can be distinguished as follows:

Two important points to remember:

In the next exercise the red cards describe various behaviors. Please sort them into what you believe is the appropriate category, i.e., universal, cultural, or personal.

We all believe that we observe reality, things as they are, but what actually happens is that the mind interprets what the eyes see and gives it meaning. It is only at this point, when meaning is assigned, that we can truly say we have seen something. In other words, what we see is as much in the mind as it is in reality. If you consider that the mind of a person from one culture is going to be different in many ways from the mind of a person from another culture, then you have the explanation for that most fundamental of all cross-cultural problems: the fact that two people look upon the same reality, the same example of behavior, and see two entirely different things.

Any behavior observed across the cultural divide, therefore, has to be interpreted in two ways:

Only when these two meanings are the same do we have successful communication, successful in the sense that the meaning that was intended by the doer is the one that was understood by the observer.

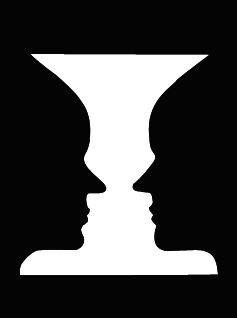

What do you see in the image below?

Is it a white vase or two faces? How do you perceive it?

In this exercise the red cards describe a series of behaviors. Sort these into categories of "Probably acceptable" or "Probably not acceptable."

Language can be both a powerful tool and a difficult barrier. Meaning is expressed not only by the actual words we say but also through our tone of voice and body language.

The percent of meaning expressed is as follows:

|

Content (words) |

7% |

|

Tone of voice` |

38% |

|

Body Language |

55% |

Things get complicated when a certain tone of voice or body language has a specific meaning in one cultural setting and a totally different meaning in another. Some examples:

Experience #1

I was living in Monterrey, Mexico working with underprivileged kids in an after-school type program. One afternoon while I was working, one of the students asked me if it was okay to move to a different activity. I said yes, but I was working with someone else at the time and apparently the student didn't hear me. The student asked once again, to which I replied with a very clear "OK" hand sign. Immediately, the student ran to another teacher and began recounting the story. The other teacher came over to ask me what had happened. I recounted the seemingly harmless events, and she promptly informed me that the child thought I had called him an a-hole for asking his question too many times. A very sincere apology ensued, and to this day, I rarely use the OK hand sign. Or at least not around impressionable children.

Experience #2

This past summer I went to Japan for 2 weeks to visit a friend. Excited for my first trip to Asia, I knew that communicating would be a struggle but that this was a once in a lifetime opportunity. Though overall I had a wonderful experience, I could have never imagined how lonely I would feel. As this was my first time visiting a country for more than 4 days where I could not communicate, I was woefully unprepared for the challenges this would pose. I stared at menus, subway maps, and advertisements feeling flat out illiterate. I had never felt so alien and out of touch and as a result struggled with these emotions. While my friend, who was working full time, did his best to help me, the fact was that there was no substitute for knowing the language.

Being an outsider is often challenging. You may enter a world with an unfamiliar language, and there may be profound differences that go beyond language. As eluded to in the Iceberg Exercise, culture exists on a variety of levels many of which are invisible at first glance.

Language, dress, greetings, family relationships, power structures, gender roles, and many other things may be very different in this new place. Students who have gone before you have shared some of their experiences with us, and their experiences illustrate some of the challenges you may face. Please take the time to read some of their unusual encounters and think about how you would react. Then see what they did or what they recommend in hindsight.

|

I hadn't timed it right. The village I had to get to was still an hour away when night fell. Walking in the dark was a nuisance; also, it had been raining since early afternoon. Worst of all, as I leaned against the wall of the chautara and felt the blessed release from the weight of my backpack, I discovered my flashlight batteries were dead. The hour ahead was shaping up poorly. As I stood there in the rain, my glasses fogged, drinking from my water bottle, an old woman came around the bend, bent over under a stack of firewood. She headed for the chautara, her eyes down, and nearly walked into me, looking up suddenly when she saw my feet. "Namaste," she said, shifting her load onto the wall. "Kaha jaane?" "To the village," I said. "Tonight? It's dark and your shirt is wet." Then, more urgently, "You're the American, aren't you?" "My son is in America," she said. She didn't look like the type whose son would be in America. "He joined the army, the Gurkhas, and they sent him there for training. Three months ago. He's a country boy. I worry. You need some tea before you go on." After ten minutes, we were at her small house beside the trail. She doffed the firewood and turned to me. "Take off your shirt." I gave her a look of surprise. She said, "I'll dry it by the fire in the kitchen. Put on this blanket." A few minutes later she came out of the kitchen with two mugs of tea, swept a hapless chicken off the table, and pulled up a bench for me. The tea worked wonders, bringing back my courage for the walk ahead. She offered me food, too, but I declined, explaining that I didn't want to be on the trail too late at night. "It's OK," she said. "You have a flashlight." She fetched my shirt. I put it on, revived by the warmth against my skin, and went outside to hoist my pack. I turned to thank her. "Switch on your flashlight," she told me. "The batteries are dead." She went inside and came back with two batteries, a considerable gift for someone of her means. "I couldn't," I said. "Besides, I know the trail." "Take them." She smiled, showing great gaps where teeth had once been. "You've been very kind to me," I said. "My son is in America," she said. "Some day, on the trail, he will be cold and wet. Maybe a mother in your land will help him."

|

Culture shock is the term used to describe the more pronounced reactions to the psychological disorientation most people experience when they move for an extended period of time into a culture markedly different from their own. The best way to get through culture shock is to see it not as an illness but as an opportunity and a natural occurrence in the process of adjusting to a culture that is different from your own.

|

The Global Experiences web page (https://www.globalexperiences.com/blog/culture-shock/) describes the phases of culture shock using the diagram shown here.

They describe the phases as follows:

"The easiest way to combat the feelings of boredom, frustration, and homesickness originated from culture shock is by creating new friendships with other program participants or locals. Global Experiences' offers multiple social events and excursions throughout the program so be sure to take advantage of them to help ease the anxiety of living in a new place. Most importantly, go explore your new city and cherish the experience!"

|

The acronym SCOUT provides a useful reminder of ways to process your experiences and information gathered during your time abroad. SCOUT. It is a five step process.

Every person's experience will be unique. This introduction to cultural competencies is meant to help make you more aware of the lens through which you view your own culture and those of others. Many people have gone before you and embarked upon their own cultural adventures. Click on the videos below to hear some of their recommendations.

Keep in mind that there is no "gold standard" when it comes to cross-cultural experiences that cultures have many aspects and levels and each experience will be different.

The majority of the content in this module comes from two sources:

Link to The Peace Corps Cross-Cultural Workbook

Link to Survival Kit for Overseas Living on Amazon.com

From the book jacket:

"For over twenty years, travelers seeking exciting and rewarding adventures abroad have looked to Bob Kohls for advice and have made Survival Kit for Overseas Living one of the most popular books ever published on crossing cultures. Kohl's penetrating insights and practical strategies on how to avoid stereotypes, how to explore the mysteries of culture, and how values and different ways of thinking influence behavior make this an indispensable guide. To bridge the cultural divide whether traveling alone or with a family, for business or education, whether staying a month or a lifetime – pack this guide first!"

Culture Clues http://depts.washington.edu/pfes/CultureClues.htm

Rachel Pitek Horta, MPH

Director of Programming and Training at Peace Corps - Costa Rica

The original version of this module was built by Xiaoli Yang, Prasanna Rao, Michael X. Lee, and Rob Schadt; with the guidance of Dr. James Wolff and Joe Anzalone: