Overview of the American Healthcare System

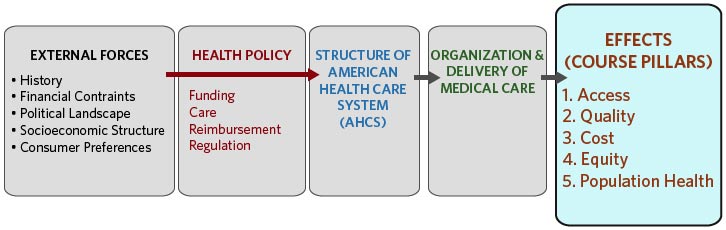

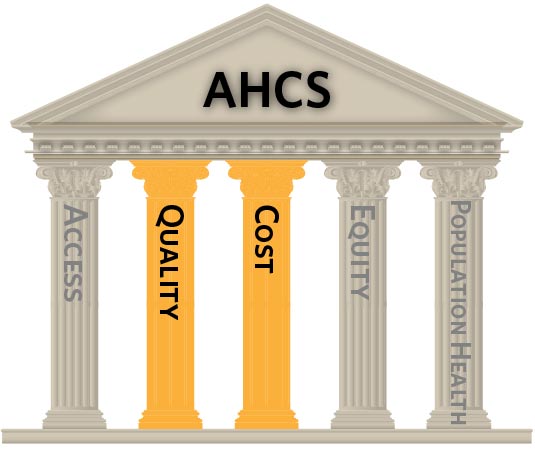

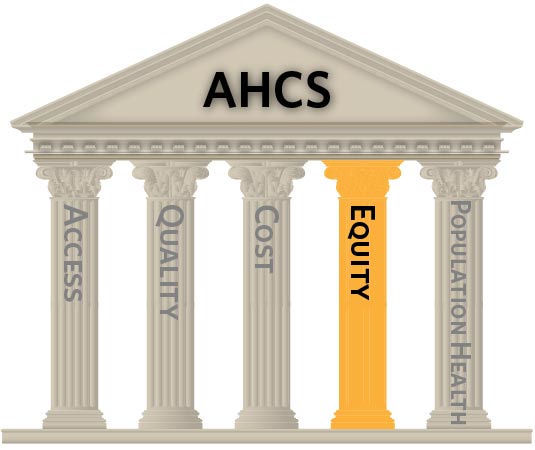

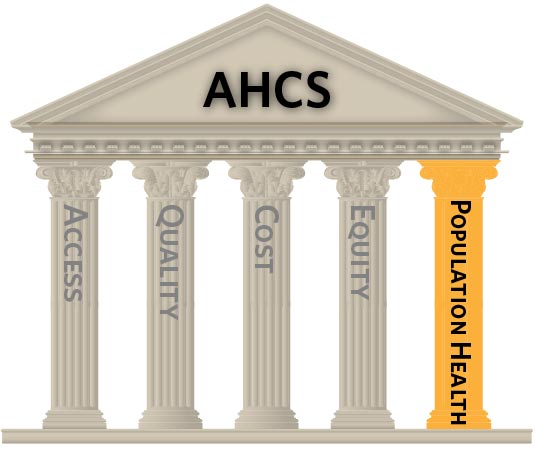

External forces of history, financial constraints, political landscape, current socioeconomic structure and consumer preferences shape the structure, or lack thereof, of the American health care system—often through health policy decisions about funding care, reimbursement, and regulation. Direct effects can be seen in the organization and delivery of care. A focus of our class will be the downstream effects on access, quality, cost, equity, and population health. These five elements of health care are the pillars of this course.

The US has the trifecta of high cost, unequal access, and often below average outcomes compared to other highly developed nations. This module will provide an introduction to the American health care system (AHCS), explore some of the complexities of health care delivery, and provide a glimpse of the historical evolution of the AHCS that has led to the great debate and need for health care reform today. We will differentiate between the traditional primary care and hospital-based paradigms and more preventive, out-patient and medical home community models.

Explore the infograph about US Health Care Costs by reviewing "Visualizing Health Policy" from the September 2012 issue of Journal of the American Medical Association. As you read, note the following:

As we move through the readings and better understand the foundations of the American health care system, we are reminded that social and institutional values and beliefs that emphasized disease more than health and prevention contributed to our astronomical costs and slowed down our progress toward attainment of a manageable and affordable system. Before we proceed, let's review a few conceptual health care models so that we are all on the same page.

Illness

|

Disease

|

How much of our poor health outcomes in the United States are due to health care. That depends on how you define health care. Watch Rebecca Onie's TED Talk below. What type of services do you think should be incorporated into health care settings.

TED Partner Series Rebecca Onie: What if our healthcare system kept us healthy?

Filmed April 2012 • Posted June 2012 • TEDMED2012

|

|

Health Care DeliveryThe United States is among the wealthiest nations in the world, but it is far from the healthiest. Although Americans' life expectancy and health have improved over the past century, these gains have lagged behind those in other high-income countries. This health disadvantage prevails even though the United States spends far more per person on health care than any other nation. Institute of Medicine. (January 2013). REPORT BRIEF U.S. Health in International Perspective: Shorter Lives, Poorer Health |

|

|

|

"Making systems work is the great task of my generation of physicians and scientists. But I would go further and say that making systems work — whether in healthcare, education, climate change, making a pathway out of poverty — is the great task of our generation as a whole."

Atul Gawande: How do we heal medicine? - TED Talks 2/2012 |

|

|

"There are too many examples that show how our system can fail to meet patients' needs. These problems are not a reflection on the many doctors, nurses and other professionals who work tirelessly to deliver the highest quality care they can. Instead, they reflect a delivery system that's not always designed with the patient in mind." Donald Berwick, Former Director of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services 7/3/2011

|

What is the health care system? What is the medical care system? Are they systems? In this course we will discuss the AHCS as if it were a unified structure. At the same time we will point out the many ways in which it is not.

|

Medical care is often understood as the more clinical aspects that take place in the traditional medical setting. Health is a much broader concept. The health care system extends far beyond the exam room and we will see this in upcoming week. For the purposes of this course we will use the term AHCS to refer to health services, health care delivery, public health, and traditional medical care |

The following table gives you an idea of the complexities of health care delivery in our country. Note that it is divided into organizations (education/research and or managed care/integrated networks), individual suppliers, insurers, providers, payers, funders, and—last but not least—the government. We will be discussing all of these components over the course of this semester, so keep this chart handy.

Though the American health care system is a far cry from being a well-oiled machine, it does have various components that are interdependent and share common goals. These components do fit into a systems model, despite all its limitations. Shi and Singh use this systems framework to illustrate some basic foundations that support the interaction between input (resources) and output (outcomes), as well as the underlying structure that supports the process dynamics, which evolve over time.

Surely, the American health care system is far from perfect, but, then, by now you probably realize that no perfect system exists anywhere. Americans have access to a patchwork of subsystems (like managed care, the Veterans Administration, and emerging IDSs) that characterize health care delivery in the US. However, the systems framework does give us at least a starting place to attempt in an organized fashion to understand an extremely convoluted, confusing, and costly health care system, and perhaps, a place to begin our quest to find acceptable solutions to our problems.

Atul Gawande is a surgeon and writer from the Boston area. Watch the video below for an academic and clinical perspective on our broken medical care systems. Focus in particular, to the questions below:

|

Atul Gawande: How do we heal medicine? |

Consider the information taken from the first chapter of a recent IOM report entitled Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America:

Access, Quality, Cost, Equity, and Population Health are the five pillars of this course. We will introduce these concepts today with an emphasis on access.

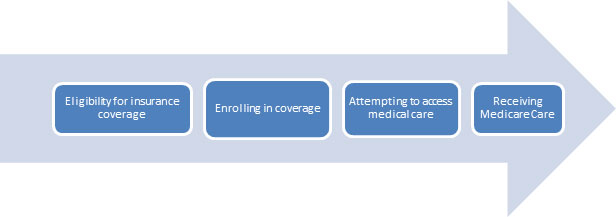

What is Access?Access in health care refers to the ability of individuals to obtain needed services. |

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) includes elements of insurance coverage through individual mandates, employer mandates (postponed until 2015) , health insurance exchanges, subsidies for low-income Americans and Medicaid expansion (only in some states) for those in poverty are intended to increase access.

We will return to the topic of Medicaid expansion in the states.

Measures of access to care may be individual or population based. These include the following:

The data for several of these measures came from the perspective of patients. When examining access from utilization remember that you are only capturing those who were able to get care. Think about the measure for 'percent of patients with lower back pain receiving an MRI.' If this is based on a review of records for lower back pain patients you only capture those people who chose to or were able to get services in the first place. This measures the rate of MRI use for back pain in a clinical setting, not in the population.

Throughout the semester we will use materials from the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) and the associated sites Kaiser Health News for current events, and KaiserEDU for health policy information.

Note: the Kaiser Family Foundation is a non-for profit foundation focusing on health policy, health journalism, and communication. There is no relationship with Kaiser Permanente or Kaiser Industries.

As we finish up on access please check to see how much you know about the uninsured in the U.S using the Uninsured Quiz from KFF. This is a tool for self-assessment and does not factor into your grade. Resist the urge to look up the answers! At the end of the quiz you will be able to view your responses, the correct answers with feedback, and links for further information.

|

The large number of uninsured people in the United States has been at the forefront of health policy discussion for decades, and in recent years has received increased attention with the passage of the health reform law in 2010. How much do you know about the uninsured population and the consequences of not having coverage? Take the quiz below to find out. |

The Institute of Medicine defines quality as "the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge".

The key components for access to quality care:

This information comes from the IOM 2001 report Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. There is much more to say about quality in health care. You could spend your career on this topic and still have more to learn. Quality will be a recurring theme, and we will return specifically to quality, evaluating quality, and quality improvement initiatives later in the semester.

Why do we care so much about cost? Because 17.2% of our spending in 2012 as a nation was on health-related expenditures. Health care costs are increasing faster than wages, which means that an increasing proportion of household income is spent on health care (premiums and out of pocket). If health care spending crowds out other spending priorities on the national or individual basis we have a problem. Are we spending too much? That depends on your perspective and spending priorities.

National Health Expenditures: total amount spent for all heath services, health research and related construction activities for one calendar year.

Gross Domestic Profit (GDP): Summary measure of the economy, could be measured in a few ways. Consider this to be how much is spent in the US on everything, including healthcare.

PDF File

|

US Annual Health Expenditures Matching Exercise |

|

In the matching exercise below, match the categories of expenditure with the numbers and dollar expenditures. You can use this file on US National Health Expenditures to help you.. |

|

|

|

Total cost = price of service ($) x number of services providedTotal cost for MRIs = cost of each MRI x number of MRIs for your customers |

What if you are in charge of buying coffee for the office? You have a machine and each cup costs the company $2. If you provide an unlimited number of k-cups there is no limit to how much you will have to spend (fee for service) method for reimbursing providers for each unit of service provided. If you put out a certain number per day you will limit the number of cups (volume), but you may not have an equitable distribution across co-workers (rationing) equitable distribution of limited resource. You could charge your co-workers a small fee per serving (cost sharing). How do you best allocate your resources (funds to buy coffee) across the group?

Now let's go to health care. You are an insurance company and you would like to spend less on MRIs next year. How do you save money? You lower the cost (price) by negotiating a better rate with an MRI vendor. Maybe you have to enter into an exclusive contract or promise a certain patient volume. You could charge patients for each test that reduces the insurance company's cost. Bottom line is that you pay less per test. You lower the volume by not paying for as many MRIs. You could require a (prior approval) requirement that provider seek approval from insurance company before providing health care services to ensure that payer will cover the expense process. Some providers may not order as many MRIs if your process is a hassle. You could increase the patient portion of the bill (cost sharing). Some patients may not be able afford this and skip the test. You could just not cover MRIs for certain diagnoses.

If you want to save money for health services you need to use less expensive services (pay less, or a cheaper service) or you can use fewer services. Think about access. Does expanding access save money? Not at the start. If you give people insurance they will likely use services.

2. Whose cost are you talking about?

Providing health insurance may save money for the newly insured. Maybe he or she now has coverage for something that used to be an (out of pocket expense) amount of money that patient pays for health care services excluding premiums. This is individual cost.

If you start to provide coffee at work you could save money for your co-workers because they will no longer go across the streets and pay for a cup. This is an example of (cost shifting).

3. Is cost all about money?

Not at all, but that will be our focus when we talk about costs this semester.

In real life there are time costs (buying coffee at the market, making it, walking to the shop) that may make one of these options more or less attractive. Maybe the shop coffee is better than what you can make. It is more expensive, but it could have more value for your dollar if you factor in taste.

We are only talking about financial cost so you are spending more if you don't make the coffee yourself. You are spending more if you don't limit how much 'free' coffee your co-workers can drink.

In health care the non-financial cost can be priceless: time, transportation, decreased work productivity, missed work, pain, quality of life, even death.

Can we increase access to care without increasing cost to the system? Not in the short term, but there could be longer-term payoffs.

Can we increase quality without increasing costs to the system? Hopefully, yes. This is a growing interest area for providers and researchers. How to we get the most value from our heath care resources.

There is a recognized need for change. The system is fragmented. Costs continue to rise. Overall, increased costs are not leading to improved health outcomes.

|

The IOM consensus report (2012) Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America highlights the challenges to our current system, and also describes some solutions. This following infographic presents the committee's goals for the AHCS. |

Improving health equity requires eliminating health disparities and improving health status for the population.

Health equity is attainment of the highest level of health for all people. Achieving health equity requires valuing everyone equally with focused and ongoing societal efforts to address avoidable inequalities, historical and contemporary injustices, and the elimination of health and healthcare disparities.

A particular type of health difference that is closely linked with social or economic disadvantage. Health disparities adversely affect groups of people who have systematically experienced greater social and/or economic obstacles to health and/or a clean environment based on their racial or ethnic group; religion; socioeconomic status; gender; age; mental health; cognitive, sensory, or physical disability; sexual orientation; geographic location; or other characteristics historically linked to discrimination or exclusion.

National Partnership for Action to End Health Disparities

|

"The United States spends more on health care than any other nation in the world, yet it ranks poorly on nearly every measure of health status. How can this be? What explains this apparent paradox?" |

In the words of Dr. Steven Schroeder in 2007 in the assigned piece titled, We Can Do Better — Improving the Health of the American People.

The two-part answer is deceptively simple — first, the pathways to better health do not generally depend on better health care, and second, even in those instances in which health care is important, too many Americans do not receive it, receive it too late, or receive poor-quality care." N Engl J Med 2007;357:1221-8.

Fast forward to today and few things have changed. In comparison to other highly developed nations we do poorly on many measures, especially for persons under age 50 years.

Consider the following two graphs that depict the causes of death of women and men in the U.S. before the age of 50, compared to peer countries.

|

|

|

|

Source: U.S. Health in International Perspective: Shorter Lives, Poorer Health |

|

The recent Institute of Medicine publication US Heath In International Perspective: Shorter Lives. Poorer Health described how Americans have worse health status and die earlier than peers in other nations. Income is known to be linked to poor health, but does not account for the differences. Persons with low income do worse, but when you compare within income groups we are still sicker and die sooner.

Think About These Issues Throughout the CourseThere is a recognized need for change. The system is fragmented. Costs continue to rise. Overall, increased costs are not leading to improved health outcomes. Can we increase access to care without increasing cost to the system? Not in the short term. Can we increase quality without increasing costs to the system? Hopefully, yes. This is a growing interest area for providers and researchers. How do we get the most value from our heath care resources. How do we tackle health disparities given the known socio-economic barrier to access to care? |