Surveillance for Infectious Disease

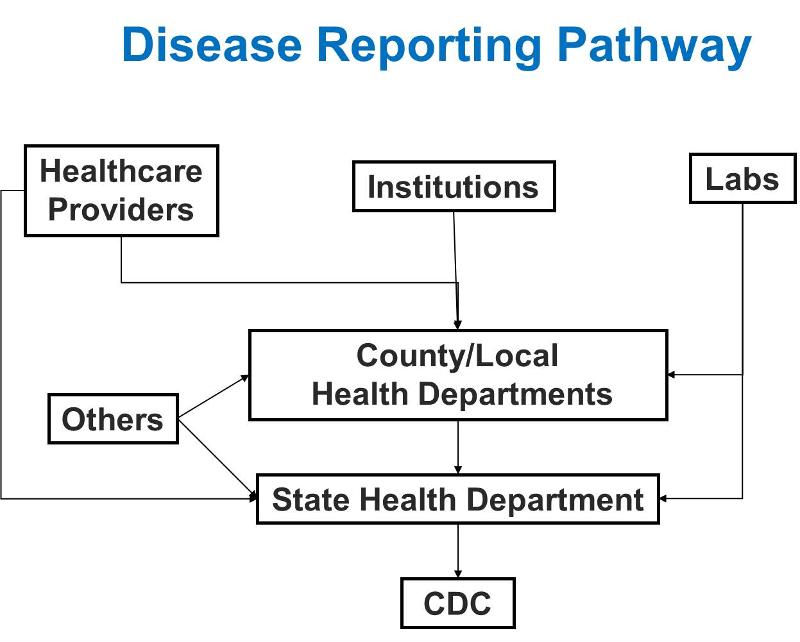

Notifiable Diseases: Each US state designates a specified list of "notifiable diseases," i.e., diseases that health care providers and/or laboratories and hospitals are required to report to the state.

In Massachusetts, local boards of health, healthcare providers, laboratories and other public health personnel must report certain "notifiable diseases" as required by law (Massachusetts General Laws, Chapter 111, sections 3, 6, 7, 109, 110, 111 and 112 and Chapter 111D, Section 6. These laws are implemented by regulation under Chapter 105, Code of Massachusetts Regulations (CMR), Section 300.000: Reportable Diseases, Surveillance, and Isolation & Quarantine Requirements.) The Massachusetts Department of Public Health provides a Reportable Diseases web site as an on-line resource for local health departments, clinical providers, hospitals, laboratories and others.

Here are links to these documents and sources:

Link to Massachusetts General Laws, Chapter 111, sections 3, 6, 7, 109, 110, 111 and 112 and Chapter 111D, Section 6.

Link to Chapter 105, Code of Massachusetts Regulations (CMR),

Link to Section 300.000: Reportable Diseases, Surveillance, and Isolation & Quarantine Requirements.

Link to Reportable Diseases web site

Link to list of reportable diseases in Massachusetts

Passive versus Active Surveillance

Passive Surveillance: While reporting is required by law, there is no practical way of enforcing adherence, so disease frequency is under reported. Nevertheless, this system has proven to be useful in identifying outbreaks and trends over time. Health care providers report notifiable diseases on a case-by-case basis. Passive surveillance is advantageous because it occurs continuously, and it requires few resources. However, it is impossible to ensure compliance by health care providers; moreover, cases occurring in people without access to care will frequently go unreported. Consequently, passive systems tend to under-report disease frequency.

Active Surveillance occurs when a health department is proactive and contacts health care providers or laboratories requesting information about diseases. While this method is more costly and labor intensive, it tends to provide a more complete estimate of disease frequency.

Massachusetts Infectious Disease Surveillance: MAVEN

The Massachusetts Virtual Epidemiologic Network (MAVEN) is a web-based disease surveillance and case management system that enables MDPH and local health departments to capture and transfer appropriate public health, laboratory, and clinical data efficiently and securely over the Internet in real-time.

National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System (NNDSS)

Data for selected nationally notifiable diseases reported by the 50 states, New York City, the District of Columbia, and the U.S. territories are collated and published weekly in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). Provision data is available online making it possible to easily look up weekly counts of reportable infectious diseases for the entire US. There are both Morbidity Tables and Mortality Tables.

Data for selected nationally notifiable diseases reported by the 50 states, New York City, the District of Columbia, and the U.S. territories are collated and published weekly in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). Provision data is available online making it possible to easily look up weekly counts of reportable infectious diseases for the entire US. There are both Morbidity Tables and Mortality Tables.

Link to the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR)

Division of Emerging Infections and Surveillance Services (DEISS

|

From the DEISS web site: "The Epidemiology and Laboratory Capacity for Infectious Diseases Cooperative Agreement (ELC) was formed in 1995 as a key component of CDC's national strategy to address emerging infectious disease threats. The program plays a critical role in strengthening national infectious disease infrastructure by providing funding to all 50 state health departments, 6 local health departments (Los Angeles County, Philadelphia, New York City, Chicago, Houston, and the District of Columbia), Puerto Rico, and the Republic of Palau to prevent, detect, and respond to new and emerging infectious diseases. With ELC support, health departments build their public health capacity by hiring and training staff, buying laboratory equipment and supplies for diagnosing emerging pathogens, and investing in information technology to improve disease reporting and monitoring. ELC investments support work on zoonotic and vector-borne diseases (particularly rabies and West Nile Virus [WNV]), foodborne diseases, influenza, antimicrobial resistance, and prion disease. The ELC has also provided health departments with the flexibility and capacity to quickly recognize and respond to outbreaks of new and emerging infectious disease threats, such as SARS and monkeypox."

|

Link to the Division of Emerging Infections and Surveillance Services (DEISS)

As an example of the utility of this overall surveillance system consider the many outbreaks of foodborne infectious disease that have occurred in the US over the past few years. In essence, each individual case of foodborne illness was reported to a local health department, and the information flowed to the state level and then to the National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System (NNDSS). The data in the NNDSS then made it possible to conduct a systematic review of changes in foodborne disease frequency over time, as reported in the publication by Scallan et al in Emerging Infectious Disease (see below).

Trends in Foodborne Illness in the United States

Foodborne Illness Acquired in the United States - Major Pathogens: Elaine Scallan, Robert M. Hoekstra, Frederick J. Angulo, Robert V. Tauxe, Marc-Alain Widdowson, Sharon L. Roy, Jeffery L. Jones, and Patricia M. Griffin, Emerging Infectious Diseases 2011;17(1):7-15. [Volume 17, Number 1, January 2011, pages 7-15]

Below there is a link to an audio pod cast of a brief interview with Dr. Scallan, the lead author of the article, in which she discusses the most recent estimates of illnesses due to eating contaminated food in the United States. Dr. Scallan is an Assistant Professor at the University of Colorado and former lead of the CDCs FoodNet surveillance system. (Running Time = 8:48)

Link to complete article in PDF.

Syndromic Surveillance

Syndromic surveillance is a relatively new surveillance method that utilizes clinical signs and symptoms that have been recorded for patients in medical treatment facilities. The premise of syndromic surveillance is that the first sign of serious acute illness in a community might be an unusual number of people seeking care for non-specific symptoms/signs. A "syndrome" is a cluster of signs and symptoms. For example, influenza is characterized by the sudden onset of fever, shivering, chills, dry (non-productive) cough, general malaise, body aches, and sometimes nausea. These symptoms could be caused by influenza or by any number of other upper respiratory tract infections, including the common cold, although flu symptoms tend to be more severe. Nevertheless, some combination of these symptoms might be defined as indicating a "flu-like illness" and the frequency of this syndrome has been found to correlate with the frequency of documented influenza. The use of syndromic surveillance is attractive because of the possibility that automated surveillance systems might be created, e.g., as described by Marsden-Haug et al. For additional information on syndromic surveillance, see the CDC web page: CDC: Syndromic Surveillance: an Applied Approach to Outbreak Detection.

Link to CDC: Syndromic Surveillance: an Applied Approach to Outbreak Detection

Link to MMWR article on Health Department Use of Social Media to Identify Foodborne Illness — Chicago, Illinois, 2013–2014link to an article about the possible use of "Yelp" to track foodborne illness.

Link to an article on the possible use of "Yelp" to track foodborne illness.

.