Research Ethics

After successfully completing this section, the student will be able to:

History is dotted with episodes in which comparisons of outcomes among groups were used to demonstrate the effectiveness of new treatments. Sometimes these were accidental experiments. Ambrose Pare was a French barber-surgeon who was a keen observer and innovator, and is regarded as the father of surgery by some. At the age of 26 (1537) he was serving in the French army in northern Italy, but he was relatively inexperienced with battlefield wounds. Pare described the aftermath of a battle:

|

"... many of our soldiers were killed or wounded by lance and shot, keeping the surgeons busy. At that time I was quite inexperienced and had never seen shot wounds treated. Certainly I had read in Jean de Vigo's general work on wounds that the properties of gunpowder made shot wounds poisonous, and that they should be treated with seething elder-oil.... To avoid doing anything crazy, and knowing that this treatment would be very painful to the victims, I decided to wait until I had seen what the other surgeons did. They actually made the oil as hot as possible and dabbed it on the wound. I then took heart and did the same, But my oil ran out, and I had to apply a healing salve made of egg white, rose oil, and turpentine. The next night I slept badly, plagued by the thought that I would find the men dead whose wounds I had failed to burn, so I got up early to visit them. To my great surprise, those treated with salve felt little pain, showed no inflammation or swelling, and had passed the night rather calmly - while the ones on which seething oil had been used lay in high fever with aches, swelling and inflammation around the wounds. At this, I resolved never again to cruelly burn poor people who had suffered shot wounds."

|

:

Link to more on Ambrose Pare

Scurvy, caused by a deficiency in vitamin C, was an enormous problem for sailors during the age of exploration. Collagen is a protein that plays an important structural role in all tissues. Humans require vitamin C from fruits and vegetables in order to cross-link collagen fibers to provide normal tissue strength. If vitamin C is deficient for long periods, such as sea voyages, tissues are weakened, and there is a tendency for capillaries to rupture easily causing bruising and bleeding with slight trauma. Severe scurvy is manifest by bleeding gums, bleeding into joints, severe anemia, and eventually cardiovascular failure and death. Commodore George Anson led a famous circumnavigation from 1740-44. He left England with seven ships and 1,955 men with the mission of harassing the Spanish fleet in the Pacific off Central and South America. He returned with one ship and 145 men. In total 1,051 sailors had died, mostly from scurvy. The East India Company had noted scurvy was common among the sailors on their ships, but one ship that carried lemons had remarkably been spared. Nevertheless, it wasn't until 1747 that James Lind, a Scottish surgeon in the British navy, designed an experiment with a purposely designated "control."

Lind selected 12 sailors suffering from scurvy and treated them in pairs with one of several 'treatments': cider; seawater; a mixture of garlic, mustard and horseradish; vinegar; or oranges and lemons. Those fed citrus fruits recovered quickly, while the others remained ill. While earlier observations had suggested the efficacy of citrus fruits, Lind's experiment established the superiority of citrus fruits over other treatments.

Link to more on scurvy

Link to more on James Lind

Another famous predecessor of modern intervention studies was Edward Jenner's experiments on the efficacy of vaccination to prevent smallpox. Smallpox had been a scourge of mankind for centuries. It had a high case fatality rate and even the survivors were left with horrible aftereffects such as blindness and disfigurement from scarring. The practice of inoculation or 'variolation' seems to have originated in Africa, India, and China, but wasn't introduced to Europe until the early 1700s by Lady Mary Wortley Montagu.

Edward Jenner had heard that dairymaids were protected from smallpox after they had contracted cowpox, a related infection. In 1796 Jenner took material from a young dairymaid's fresh cowpox lesions and used it to inoculate an 8-year-old boy, James Phipps. Phipps developed a mild fever, soreness in his armpits, and loss of appetite, but recovered about a week later. About two months later, Jenner inoculated the boy with fresh smallpox pus, but he did not become ill, and Jenner concluded that the cowpox "vaccination" had protected the boy against smallpox. While this is regarded as a landmark event in the prevent of infectious disease, one should question the ethics of conducting this experiment.

Link to article: Edward Jenner and the History of Smallpox Vaccination

Human subjects are essential to research efforts to improve human health, but, no matter how lofty the goals of the research, it is not ethical to use people as a means to an end.

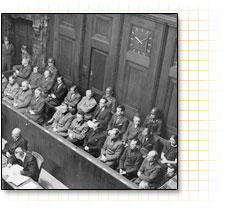

There have been many examples of unethical research, but world wide attention became focused on the experiments conducted by Nazi physicians during World War II. Experiments involving a wide variety of deadly, painful, and disfiguring procedures were conducted on thousands of concentration camp prisoners. In 1946, the War Crimes Tribunal at Nuremberg indicted 20 physicians and 3 administrators (photo to the right) for their willing participation in these experiments. The verdict at Nuremberg included ten directives for human experimentation that have become known as the Nuremberg Code:

|

The Nuremberg Code

|

The atrocities performed by physicians in the Nazi concentration camps prompted the World Medical Assembly to discuss guidelines for physicians engaged in medical research. Their ethics committee began considering this in 1953, but it wasn't until 1964 that the WMA adopted "Recommendations guiding physicians in biomedical research involving human subjects," at their 18th congress meeting in Helsinki, Finland. These guidelines have become known as the Declaration of Helsinki. These have been updated and revised a number of times.

Link to more on the World Medical Assembly

Link to more on the Declaration of Helsinki.

The United States Public Health Service conducted a study on the natural history of untreated syphilis in Tuskegee, Alabama from the 1930s until 1972. Approximately 600 African-American men (about 400 with syphilis and about 200 without syphilis) were recruited into the study without informed consent and were misled into thinking that some of the experimental testing procedures, such as spinal taps, were "special free treatment." By 1936 it had become clear that problems were more frequent in the infected men, and after ten years it was known that the death rate was twice as high in the men with syphilis. Penicillin was shown to be an effective treatment for syphilis in the 1940s, but the study continued, and the subjects were not given penicillin or even informed about its availability. The press aired the story in 1972, and this provoked public outrage.

The United States Public Health Service conducted a study on the natural history of untreated syphilis in Tuskegee, Alabama from the 1930s until 1972. Approximately 600 African-American men (about 400 with syphilis and about 200 without syphilis) were recruited into the study without informed consent and were misled into thinking that some of the experimental testing procedures, such as spinal taps, were "special free treatment." By 1936 it had become clear that problems were more frequent in the infected men, and after ten years it was known that the death rate was twice as high in the men with syphilis. Penicillin was shown to be an effective treatment for syphilis in the 1940s, but the study continued, and the subjects were not given penicillin or even informed about its availability. The press aired the story in 1972, and this provoked public outrage.

In the United States the outrage over the Tuskegee Study resulted in passage of the National Research Act of 1974 and the establishment of a Health and Human Services Policy for Protection of Human Research Subjects. As a result, all US research involving human subjects must now be reviewed and approved by an Institutional Review Board (IRB). Subjects must voluntarily give their informed consent to participate in a research trial. "Informed consent" means that the subjects must be fully informed and understand all aspects of the research including the nature and objectives of the study, the treatment options, the risks and benefits, the data to be collected, the methods by which treatment assignments will be made, etc. Informed consent must be obtained before assignment to a treatment group.

The Tuskegee Study also prompted the establishment of the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, which was charged with identifying the basic ethical principles that should be adhered to in the conduct of research involving human subjects. In 1978, the Commission published "Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research," also known as the Belmont Report. The Belmont Report identified three fundamental ethical principles for all human subjects research:

Link to the Belmont Report

Link to General Requirements for Informed Consent

The Health and Human Services Policy for Protection of Human Research Subjects in the Code of Federal Regulations defines human research as follows:

Research means a systematic investigation, including research development, testing and evaluation, designed to develop or contribute to generalizable knowledge. Activities which meet this definition constitute research for purposes of this policy, whether or not they are conducted or supported under a program which is considered research for other purposes. For example, some demonstration and service programs may include research activities.

Human subject means a living individual about whom an investigator (whether professional or student) conducting research obtains:

Is important to note that ALL human research must be reviewed and approved by an IRB before a study is begun. This applies to observational studies and descriptive studies as well. Even if a study involves only collection of pre-existing data, e.g., based on a review of medical records, there is the possibility of harm to the subjects from research staff collecting potentially sensitive information. The definition of human research is intentionally broad, but it excludes "de-identified" information.

Link to the Policy for Protection of Human Research Subjects

Link to more on Institutional Review Boards (IRB).

Link to US Health and Human Services and Code of Federal Regulations on Protection of Human Subjects

See also:

Brief outline of IRB Application Requirements at Boston Medical Center

Article by Janice Weinberg and Ken Kleinman on Good Study Design and Analysis Plans as Features of Ethical Research with Humans

The IRB requirement is not a general requirement but rather is required of federally funded research institutions. Thus, IRB approval is required for human research that is federally funded or is being conducted by an entity that otherwise receives federal research funding. The web site for the federal office that oversees these matters is located at the following link: http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/. A particularly helpful page is the following link: http://answers.hhs.gov/ohrp/categories/1563, which discusses the assurance process and the kind of institutions that must have IRBs because they conduct research that is regulated by the feds. The most relevant part says,

"HHS human subject protection regulations and policies require that any institution engaged in non-exempt human subjects research conducted or supported by HHS must submit a written assurance of compliance to OHRP. The Federal wide Assurance (FWA) is the only type of new assurance accepted and approved by OHRP. FWAs also are approved by the Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP) for federalwide use, which means that other federal departments and agencies that have adopted the Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects (also known as Common Rule) may rely on the FWA for the research that they conduct or support. Institutions engaging in research conducted or supported by non-HHS federal departments or agencies should consult with the sponsoring department or agency for guidance regarding whether the FWA is appropriate for the research in question."

Link to HHS policy definition of engagement of an institution in human research

However, even if you are not required by federal requirements to have your research reviewed, the funding agency may require it. Furthermore, even if you are not required to have this research reviewed by an IRB, you should feel ethically bound to protect your subjects, and the federal rules set good standards that are worth paying attention to. The federal regulations can be found here at the following link:http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/human subjects/guidance/45cfr46.html#46.103

In the 1950s when case-control studies indicated an association between smoking and lung cancer, it would have been unethical to test this with a randomized clinical trial, because there was strong suspicion that smoking was very harmful and of little or no benefit. An important factor in determining whether it is ethical to conduct a clinical trial is "equipoise," which means a balance in which one has sufficient doubt that the treatment is beneficial (justifying withholding it from some subjects) balanced against sufficient belief that it is beneficial (justifying giving to some subjects). Timing of clinical trials can be important, because once the lay public takes up a belief in a new treatment, it may be impossible to rigorously test its efficacy with a clinical trial.

When evaluating a new treatment, a major issue is the comparison group. For example, if you are evaluating a new treatment for leukemia, should the control group consist of leukemia patients who are untreated, or should it consist of patients who are being treated by the usual therapy? When should an inactive agent be used, and when should the currently accepted therapy be used as the standard against which one compares the benefits of a new treatment?

The Declaration of Helsinki clearly states:

Link to Declaration of Helsinki

These principles seem to firmly establish that placebo treatment should never be used when an accepted standard of care exists. In such a case a new therapy should also be compared to the accepted standard of care in order to determine whether the new therapy has advantages over the standard treatment. Nevertheless, there was substantial debate about this when trials were proposed in the 1990s on new treatments to reduce maternal to child transmission of HIV. Previous studies had demonstrated the zidovudine administered to HIV-positive pregnant women reduced the risk of transmission to their children. A series of new trials were proposed to test the efficacy of shorter courses of ziduvodine and other variations. Many of these trials were funded by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) or Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The two tables below contains excerpts from articles presenting different perspectives on this issue. The first was an article by Harold Varmus, M.D. (Director of NIH at the time), and David Satcher, M.D., Ph.D. (Director of CDC at the time) in which they defend the studies proposing the use of a placebo-treated comparison group, largely on the basis that no therapy was available for the vast majority of people in Africa, because they couldn't afford it. The second article was written by George J. Annas, JD, MPH, and Michael A. Grodin, MD from Boston University School of Public Health, in which they attack the proposed trials as unethical. Read the excerpts and the articles in order to determine what you think and what you would decide. Try to list the ethical principles and precedents that may be relevant.

Ethics and Studies of HIV

|

Excerpts from "Ethical Complexities of Conducting Research in Developing Countries" by Harold Varmus, M.D., and David Satcher, M.D., Ph.D. N Engl J Med 1997; 337:1003-1005, October 2, 1997.

"... the NIH- and CDC-supported trials have undergone a rigorous process of ethical review, including not only the participation of the public health and scientific communities in the developing countries where the trials are being performed but also the application of the U.S. rules for the protection of human research subjects by relevant institutional review boards in the United States and in the developing countries. Support from local governments has been obtained, and each active study has been and will continue to be reviewed by an independent data and safety monitoring board. To restate our main points: these studies address an urgent need in the countries in which they are being conducted and have been developed with extensive in-country participation. The studies are being conducted according to widely accepted principles and guidelines in bioethics. And our decisions to support these trials rest heavily on local support and approval. In a letter to the NIH dated May 8, 1997, Edward K. Mbidde, chairman of the AIDS Research Committee of the Uganda Cancer Institute, wrote:

These are Ugandan studies conducted by Ugandan investigators on Ugandans. Due to lack of resources we have been sponsored by organizations like yours. We are grateful that you have been able to do so. . . . There is a mix up of issues here which needs to be clarified. It is not NIH conducting the studies in Uganda but Ugandans conducting their study on their people for the good of their people."

|

|

Excerpts from "Human Rights and Maternal-Fetal HIV Transmission Prevention Trials in Africa" by George J. Annas, JD, MPH, and Michael A. Grodin, MD, Am. J. Public Health 1998;88(4):560-563.

"In 1994, the first effective intervention to reduce the perinatal transmission of HIV was developed in the United States in AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG) Study 076. In that trial, use of zidovudine administered orally to HIV-positive pregnant women as early as the second trimester of pregnancy, intravenously during labor, and orally to their newborns for 6 weeks reduced the incidence of HIV infection by two thirds (from about 25% to about 8%). Six months after stopping the study, the US Public Health Service recommended the ACTG 076 regimen as the standard of care in the United States. In June 1994, the World Health Organization (WHO) convened a meeting in Geneva at which it was concluded (in an unpublished report) that the 076 regime was not feasible in the developing world. At least 16 randomized clinical trials (15 using placebos as controls) were subsequently approved for conduct in developing countries, primarily in Africa. These trials involve more than 17 000 pregnant women. Nine of the studies, most of them comparing shorter courses of zidovudine, vitamin A, or HIV immunoglobulin with placebo, are funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) or the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Most of the public discussion about these trials has centered on the use of placebos. The question of placebo use is a central one in determining how a study should be conducted. But we believe the more important issue these trials raise is the question of whether they should be done at all. Specifically, when is medical research ethically justified in developing countries that do not have adequate health services (or on US populations that have no access to basic health care)? |

Consider the arguments presented in the two articles referenced above. After reading these articles, consider the issue in light of the principles discussed in the section above on the ethics of conducting clinical trials. Consider the principles established by the Nuremburg Code, the Declaration of Helsinki, and the Belmont Principles. Which position would you choose, based on the principles that have been established?

For additional commentary, see Dr. Marcia Angell's editorial on The Ethics of Clinical Research in the Third World in the New England Journal of Medicine (1997).

See also this video from TED.com in which Boghuma Kabisen Titanji discusses the ethics of doing HIV clinical trials in resource-poor settings.(Filmed in May 2012; posted Jan. 2013.)

Placebo effects can also occur when evaluating the efficacy of a medical device or a medical or surgical procedure. A logical way of evaluating efficacy in this setting would be to perform a "sham" procedure. For example, some investigators believed that Parkinson's disease could be effectively treated by transplantation of fetal tissue into the human brain, a procedure that required anesthesia and drilling holes into the patient's forehead in order to introduce fetal cells into the brain. Olanow et al. enrolled 34 Parkinson's patients into a double-blind study in which patients were randomly assigned to receive fetal cells or a "placebo" surgical procedure. The sham procedure was believed to be necessary to determine whether there was a placebo effect. The investigators found no significant difference between those receive fetal cells and those who did not. The concern, of course, is that the sham-treated subjects are being undergoing general anesthesia and a potentially risky neurosurgical procedure, but without any real expectation of a genuine, lasting benefit. Nevertheless, the IRB and the investigators justified the sham procedure on the basis that it demonstrated no benefit of the transplantation; as a result, it prevented countless numbers of Parkinson's disease victims from receiving a costly, invasive procedure that had no benefit.

Link to article by Olanow et al.

To explore the ethics of using sham controls in greater detail, see the following articles: